What Happened After Urban Renewal

At least 500 homes were expected to be destroyed, and at least that many families displaced.

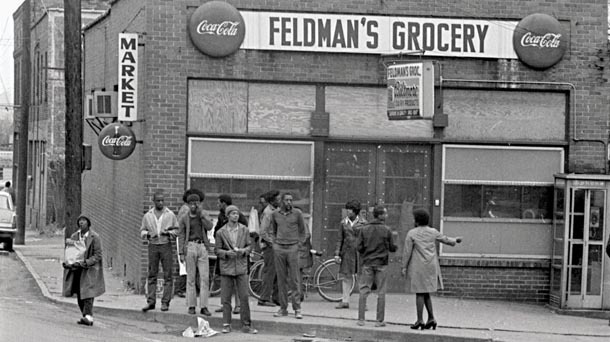

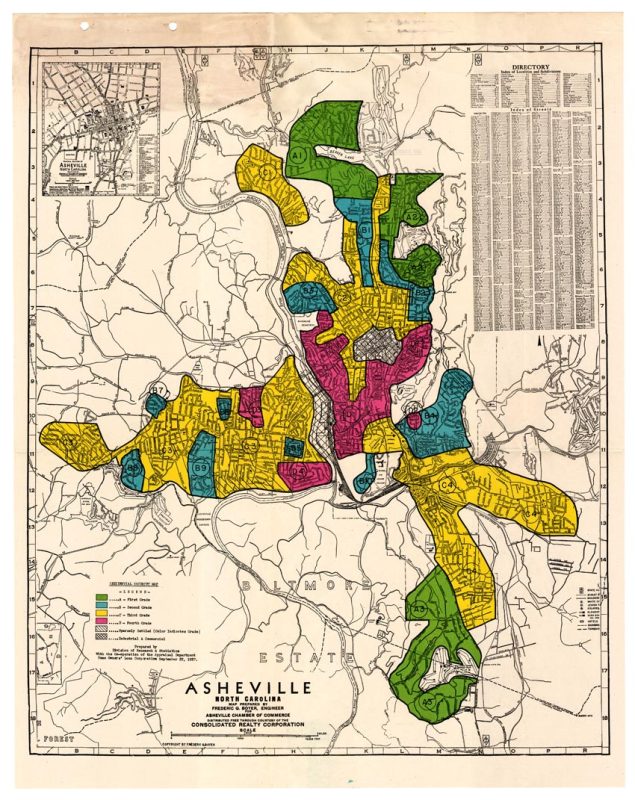

Beginning in the 1960s, multiple federally funded Urban Redevelopment projects significantly reshaped historically Black neighborhoods, including Southside, East End/Valley Street, Hill Street, and Stump Town.

Rechristened the East Riverside Project, what had been the Southside Redevelopment Project would include approximately 400 new public housing apartments to be built at a cost of $6 million to $8 million, using primarily federal funds. Although at least 500 homes were expected to be destroyed, and at least that many families displaced, the Asheville Redevelopment Commission determined that only 400 units would be needed—with 75 of them set aside for the elderly.

Meanwhile, the destruction of entire neighborhoods began. Sometimes house by house, other times street by street or block by block, the properties were appraised at what many considered far below market value.

An early indication of how the urban renewal process would be viewed by the men and women who pushed for it came with the resignations of the director and assistant director of the WNC Regional Planning Commission and the city’s and county’s joint Metropolitan Planning Board. Less than six months after the “East Riverside/Southside” project was approved in July 1964, Robert D. Barbour resigned as director of both agencies, and Gary M. Cooper resigned as assistant director. Both had been hired in April 1963, just 15 months before.

“In their letters of resignation,” reported the Asheville Citizen on Dec. 9, 1964, the men stated “they intend to establish a private city and regional planning operation in Asheville.”

Then … surprise, surprise … the two men bid for a $72,000 contract from the Metropolitan Planning Board, aiming to grab $72,000 of the $162,000 authorized by the US Housing Agency to pay for a survey of the city. It seemed that, after the two men had quit their jobs, “the local planning staff if not equipped to undertake the work,” wrote the Citizen.

It would be wrong to assume that all, or even a majority, of the participants in the Urban Renewal program were as self-serving or apparently unethical as Messrs. Barbour and Cooper; ample evidence exists that many of those involved truly did aim to improve lives and opportunities for residents. And while it’s impossible to read the hearts of others, actions can provide guideposts. For example, the Asheville Redevelopment Commission adopted a resolution binding itself to observe racial non-discrimination provisions of the Federal Civil Rights Act of 1964 (enacted the previous July).

Similarly, one of the editorial writers in The Asheville Times wrote: “More deeply, [vandalism and crime] is also a community social problem. … Police work alone will never solve this problem, necessary though it is. It takes the long view to see the neglected small child in a poor family as the future teenage enemy of society.

“There is a need for better social services to poor families, and for preschool training for their children. … for more recreation in slum neighborhoods and public housing projects. By definition and requirement, families in housing projects are at the bottom of the income scale. It is unrealistic not to expect them to have a high percentage of social problems. As of now, remedial and preventive services are extremely meager…”

And in fact, in his 1965 push for additional urban renewal money, President Johnson requested subsidies for housing payments for low-income families. That money, The Wall Street Journal wrote, would pay the difference between a family’s resources and its rental costs, “on the theory that a family shouldn’t have to spend more than 20% of its income for housing.

For a family with an annual income of $3,000 [typical for that era], for instance, 20% of its income would be $600. If the rent required for its housing were $800 a year, the Government would provide the $200 difference, paying it to the sponsor rather than to the family. For a family buying an individual unit … the subsidy would make up the difference between the mortgage payments and 25% of its income.”

Johnson also asked for funds to pay for the repair of “rundown individual homes” in order to save them from urban renewal bulldozers. “Low-income families could receive grants of up to $1,000, as well as low-interest-rate loans,” according to the Journal. Money was also to be allocated to purchase undeveloped land in urban areas, “to create small parks and squares, malls and playgrounds.”

This vision reimagined poor neighborhoods not as slums to be removed but as neighborhoods to be renewed … and improved. For Johnson, urban renewal was a way to fulfill the promises of the Civil Rights Act of 1866 as well as that of 1964. It was, at least within its origins, well intentioned. And yet it went so wrong.

As one Asheville resident wrote in a contemporary letter to the editor, “Homes have been condemned and people have been put out who were born and reared in these very homes. Many of these have been houses that have been kept in good repair. …

I know that I speak for others when I say that I resent having to admit strangers, permit them to prowl over the entire house, counting rooms, windows, doors, electric outlets and even peer into closets …

Moreover, they must know age, income, source of income, how much we owe! I feel that no government, city or Federal, has any right to invade the privacy of homes.”

Politics

Reuben Dailey announced his candidacy for the Democratic nomination to City Council; 8 seats are to be voted on, and the Dem Party had already put forth a slate of seven candidates (all white?) Dailey, who served as Secretary-treasurer of the Redevelopment Commission, lost, but all seven white Democrats won.

Shortly afterward, Dailey’s supporter W.E. Roland was named by the Redevelopment Commission to a $7,500 per year job as rehabilitation administrator. The five Black committee members of the heavily Black 10th Precinct, based at Livingston Street, resigned in protest, considering Roland, an African American jeweler, unqualified. Roland acknowledged he did not have even a high school certificate.

In his support for Roland, Dailey claimed that the commission had been “unable to find a Negro applicant with a college degree.” As they resigned en masse, the five Black Democrats—Precinct Judge Eugene Smith, publisher of the Southern News; Chair Pauline Gilliam; registrar Willie Ford Hennessee; poll clerk Cordelia Graham; and machine clerk U.S. Graham—Smith noted that among the Black candidates who were passed over for the job were a lawyer, an architect, and a third candidate with a master’s degree.

On April 7, 1965, The Wall Street Journal quoted a Federal Housing and Home Finance Agency survey of 2,300 families displaced by urban renewal that asserted that 94% had “re-established themselves” in “standard” housing elsewhere. Among the problems pointed out by the Journal were that median monthly rent “rose from 12% from $66 to $74; 34% said shopping was less convenient; 29% found public transportation less satisfactory; and 45% are farther from their church than before.” The Journal, of all conservative papers, wrote: “The agency’s own study does little to remove the worry that, in the Government’s rush to make over cities, a lot of people are still getting run down by its bulldozers.”

A prescient editorial was made by Smith as he wrote in The Southern News on April 30, 1966:

“We received a letter April 19, 1966, signed by Mr. James W. Greer, executive director [of the Asheville Redevelopment Commission], asking us to give them an opportunity to [explain] what they are doing in the E. Riverside Project. … Members of his staff are talking out of both sides of their mouth. On one side of the street they are telling people to improve their homes—and on the other … they are telling people they cannot improve.

“[The] people in this area are not satisfied with the set-up. We cannot understand how the city council can continue this type of program another year. Not one home has been improved under the direction of this outfit. It is often that the many hundreds of Negroes have been sold down the river by some Negro who has been hired and he nows that he is not interested in better homes for Negroes. Not only about Mr. Roland, this newspaper will appreciate the other members of this staff and their qualifications be told about. If this office is continued, funds are being raised to send a delegation to Washington to ask for an investigation into this E. Riverside Project.”

By May 1966 the Metropolitan Planning Board had received recommendations for nine additional urban renewal projects at a total price tag of $21 million—two-thirds to be paid by federal funds, the balance locally. Almost all nine areas were primarily African American residential districts, and all of them considered “blighted.”

- 84 acres along Burton Street;

- 35 acres along Cumberland Avenue north of the Crosstown Expressway (this would be dropped if the “new convention and civic events center” were to be built;

- West End south of Patton and west of Clingman Avenues (105 acres);

- Hill Street north of the Crosstown Expressway (62 acres);

- Eagle Street (24 acres);

- Catholic Hill, east of Eagle Street (147 acres);

- Dalton Street area adjacent to Kenilworth (31 acres);

- Morrow Street, north of Riverside Cemetery (23 acres); and

- the central business district bounded by Rankin Avenue, College Street, and Lexington Avenue.

The proposal also called for a county-wide redevelopment commission to address “blighted areas” outside the city limits.

Strangely, and reflecting a desire for social “improvement” by progressive groups—or at least the desire to be perceived that way—the proposal urged the development of a “total renewal” program that would seek “human social renewal” as well as physical redevelopment. The proposal also called for added parks, pedestrian malls, and other urban beautification.

To no one’s surprise, this proposal was prepared and presented by “Barbour-Cooper Associates,” the firm established by the two former city planning directors who had found a way to personally profit from their insider knowledge of the city’s program.

In a presentation to the “Commerce Boomer Club” of the Chamber of Commerce, Greer compared deterioration of housing in the “blighted” neighborhoods identified by Barbour and Cooper to “what cancer cells are to the health of a person. Without treatment, blight spreads.” He went on: “Left alone, blight will engulf all of East Riverside. The shacks and shanties, the stench and smell of decay, will infect the entire area, and it will become even more a festering sore on the face of Asheville.”

He acknowledged “a nucleus of proud and intelligence citizens … who would seize the opportunity of transforming their neighborhood… We have at hand the opportunity. It is upon us who have the means to provide these people the tools of renewal of new life.”

Yet none of what was proposed included “tools of renewal”; rather, those who owned property, no matter how “blighted” or poor, were forced to sell it for pennies on the dollar and then offered rental apartment to live in. Thus, whatever equity they had slowly acquired over decades was quickly stripped from them, and many families were condemned to generations of reliance on city “generosity”—subsidized rent rates—rather than building value for themselves.

When it came time to move forward with the plan, the ARC did, apparently, make real attempts to reach out to the residents who would be relocated. On June 1, 1966, a public meeting was held on S. French Broad Avenue with several hundred residents in attendance. Greer and Dr. Joseph Chandler, chairman of the Housing Authority, called the new low-rent apartments “public housing that I think you are going to be proud of,” describing the units as “like nothing ever seen before.” A local resident, W. C. Allen of Southside Avenue, moved to accept the proposal, and the crowd, according to the Asheville Citizen, “voted unanimously” in favor.

Similarly, a Chapel Hill consulting team was hired to develop a “diagnostic survey” to collect information about the preferences of area residents for the program. The firm brought in two men from Chapel Hill who began meeting with neighborhood groups and individuals to determine what questions and concerns were to be addressed; they then hired 50 residents of the neighborhood to “knock on doors” to carry out the survey.

But, as the Southern News wrote in an editorial shortly after the public meeting:

“500 public houses are to be built in this area; it would be 6 to 8 years before they are completed.” Meanwhile, he wrote, “The Asheville Housing Authorities have on the way 0200 public units in the Southside area. We already have 96 units in the Southside area. 200 more will be 296. 500 more will be 796. Are all the Negro citizens of Asheville planning to live in public housing?”

City Council pushed ahead and approved the East Riverside project on June 24, 1966, on a 5-1 vote. The dissenter, Theodore Sumner, asserted that, rather than using federal funds and investing $1.4 million city dollars—to be raised as a public bond, paid for with a 7-cent property tax increase—the city should strictly enforce the housing code “to tear down 100 houses a year.” He offered no way to replace those houses, however, or any provision for housing the families who would lose their homes.