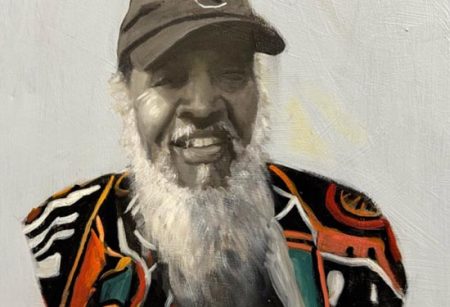

Reflections of a Caregiver

If your loved one shows signs of dementia or memory disorder, research the assisted living facility you are considering.

My journey as a caregiver for my loved one started in 2006 when she fell and fractured her hip.

by Sharon Kelly-West –

Though she recovered well, the injury influenced her decision to not drive again, and my role as caregiver was punted into the next level.

My priorities gradually shifted from what I planned to do on my list, to what I must do on her lists—which were usually not long, but were time intensive. She did not have many medical appointments, and at the age of 77 at that time, was taking only two prescription medications. She insisted on going to the grocery store rather than having me shop for her. She insisted upon using a cane for walking—with an adamant “no” to a walker. A few times she tried Mountain Mobility, but she did not like being in the van for long periods of time.

In time, she transitioned from the cane to a walker for greater stability; but after that, she preferred to not leave her home, in part for fear of folks seeing her with a walker, or of not getting to the bathroom in time, or folks seeing her difficulties in standing up. I shared with her many times that it does not matter what others thought, and I reinforced that “we are a team and are in this together.”

She did love going for sightseeing rides in my car, and going out to eat at her favorite spots. Today I recall the humanity we experienced in restaurants we visited. When I could no longer assist her to a standing position alone, I became bold in asking complete strangers, “Can you help?” No one ever said to me, “Nope, can’t do it.” Not once. Instead, they would applaud her for coming to the restaurant to enjoy the food. To those total strangers who were there when I reached out, I say, “Thank you.”

Perhaps three or four years later, I began finding notes she would leave in her home, reminding her to do those things I thought would come naturally—get the paper, call Sharon. She was always a planner and a list maker, so at that time I did not see it as suspicious. But then I noticed she began accusing people, mostly me, of taking her purse, or removing money from it, or—and this was a red flag—tampering with food or drink in the refrigerator.

So I reached out to Memory Care (experts in dementia and memory loss). I was very familiar with their compassionate work in our community, but this was the start of my education on Dementia 101.

About six years ago, my loved one said to me outta nowhere, “Sharon, don’t you think I should go some place where there are people I can socialize with during the day?” It was a gift that she mentioned this, as I was thinking, and reading, about how lack of socialization can negatively impact a person’s mental status. I worked during the day and she was at home watching TV or reading the newspaper, because most of her neighbors also worked during the day. Yet she had the wonderful insight to know something was changing inside her sharp mind.

At that point, we went—together—to view assisted living facilities. We decided on one great place, but I was not comfortable with their knowledge about caring for anyone with possible early dementia. I was there daily, and over the following two years, her needs progressed. She still had not been officially diagnosed with dementia by her primary care doctor—the signs she was exhibiting were attributed to being elderly. Because of my familiarity with Memory Care and their awesome team, I asked the Assisted Living facility doctor (I actually told him) to arrange a Memory Care assessment of her for mild dementia.

I will not ponder why the medical doctor at the Assisted Living facility did not think of this first; I will say only that you must advocate for your loved ones. Memory Care did intervene, thank God, and when my loved one outgrew the Assisted Living level of care, she qualified for a Skilled Nursing facility. To identify the facility best suited for her, I visited unannounced (pre-Covid) in the early morning, afternoon, and late evening to see the condition of residents at various times.

I then identified the one facility that met most of the criteria I established to keep her safe. She could fend for herself, yet was vulnerable; we also described her often as “spicy.” The staff welcomed input from me—and though a great facility, I felt it necessary to visit daily.

A year ago, I noticed a decline that was triggered during the Covid debut in 2020. Pandemic restrictions permitted no in-person visits; I could only view her through a window as I stood outside to blow her kisses and speak slowly and loudly so she could hear me.

Eventually, I was allowed to visit (I was forced to update the facility administration on new laws allowing “compassionate care” visits which must be honored): we were still not allowed to touch and had to sit six feet apart. (However, I would sneak in a hug and a kiss when staff looked away. Her kisses on my cheek were like wisps of a butterfly’s wings.)

Then I noticed her eating and drinking less, and she began speaking of wanting to “go” (death). At first I attempted to re-direct the conversation, but I knew I needed to acknowledge this next journey. So I called in the experts. At Four Seasons Hospice, her nurse, Brandon, was the best nurse imaginable: he visited often and chatted with her and listened as she spoke of her life. He loved serving her. She still exhibited that “spice” that only Edythe Elizabeth Webb could deliver.

On December 27 at 1:30 p.m., I walked into her room as the staff were preparing to move her to provide more privacy for us. Life was slowly but steadily leaving her body. I insisted that she not be moved: the staff meant well, but moving her as she was actively transitioning could not be allowed. She was familiar with that environment, where she felt warm and safe.

My final act of advocacy was to protect her “spiritual space.” Though nonresponsive, she was spiritually and emotionally aware of all that was happening around her as her respirations became farther and farther apart. This journey would not, will not be interrupted. Three hours later, on December 27, 2021 at 4:45 p.m., Mommy breathed her last breath, at peace, and I was there with her. It was a beautiful ending to a long journey. And, yes, we did this together!

Here are my reflections

Socialization is key—if possible, locate places for your loved one to engage. Do this together. Take them to restaurants and for rides. Spend time with them. You will not regret it.

Do your research. If your loved one shows early signs of dementia or memory disorder, make sure the facility you are considering is equipped to work with this population. If a skilled facility is in order, visit the facility at different times of the day. Are the residents dressed and with toiletry needs met? Are those who need assistance with feeding sitting in a hallway or in their room with trays in front of them and the food cold? Are the residents in bed with bed covers totally in disarray and hair unattended in the middle of the day?

Journal your journey. You will forget those encounters you felt you would never, ever forget. Write down your loved one’s responses (there were so many funny moments we would laugh together about).

Step back to monitor your personal wellness. Take long walks, watch movies—especially those that make you laugh. Listen to your body. Identify people who can visit your loved one on those days when you must simply be still. Take a nap daily to refresh.

There is much more to share, but now, for me, it is time for counseling. I miss her every day. Yet, I know she is at peace. Do not be afraid or ashamed to go for counseling at any time—definitely during periods of grief. Make time for this. You are worth it.

Mommy, thanks for the journey!