Son of the South

by Russell B. Hilliard, Sr.

by Russell B. Hilliard, Sr.

One of our nation’s most sobering memorials is found in the many- faceted city of Atlanta. I have visited this shrine to non-violent change three times, and have felt the same awe and wonder in each of my visits. I believe that any American would not only be made more aware of the depth of our prejudices, but also of the width of our progress, if he/she would spend half a day in the shade of the skyscrapers visiting the Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial in Atlanta. These are some musings from my first visit to this extraordinary American memorial.

I made a trip to Atlanta today, and it became a

pilgrimage into my past. It was a memorable day, with my friends Angel,

Job, and Rodolfo. We made the journey to obtain their Mexican

passports. Since we needed to wait for approximately five hours for the

passports to be processed, Angel suggested a visit to the memorial of

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Angel and I had hurriedly passed by Auburn

Avenue and the stately memorial on an earlier trip, and I had promised

him a return visit at a future time.

From the moment we entered the new visitor parking area, beautifully

cared for by the National Park Service, feelings began to stir within

me. As we four walked down the Gandhi promenade towards the Visitor’s

Center and read excerpts from Dr. King‚s addresses, I knew this was

going to be a different kind of day. Upon entering the Visitor’s

Center, I sensed immediately that this son of the South was going to be

shaken in this shrine to non- violent change.

In a striking museum setting, the years of the 1960s are dramatically

displayed by means of photographs, statues, and — by far the most

moving — by live news accounts. I watched as young African Americans

were arrested, beaten, pulled, and shoved in the “sit-ins” of Nashville

and Greensboro. I attempted to translate for my Mexican friends the

“freedom rides,” of Louisiana and Mississippi, the “bus boycott,” in

Montgomery.

Then, for the first time ever, I saw and tried to interpret the arrests

of 700 persons in Albany (very near to my own hometown in South

Georgia). Narrated by newscasters of the day, like Walter Cronkite, by

ladies who had been little girls at that time, and by Congressman John

Lewis, the impact of these scenes was beyond imagination. I tried to

translate for Angel, Job, and Rodolfo, but I broke as we viewed the

horses charging and the people bleeding on the bridge in Selma, the

dogs attacking and the bombs blasting the churches in Birmingham.

I asked my Mexican friends to forgive me, and I went into the restroom

and wept there deeply within. Some of the tears were sad ones from this

son of the South. I was left stunned and sorrowful at seeing evil so

openly sanctioned in my generation. Yet some of the tears were healing:

just to know that someone had been willing to pay the enormous price

for freedom, for the civil rights of us all in our great country!

|

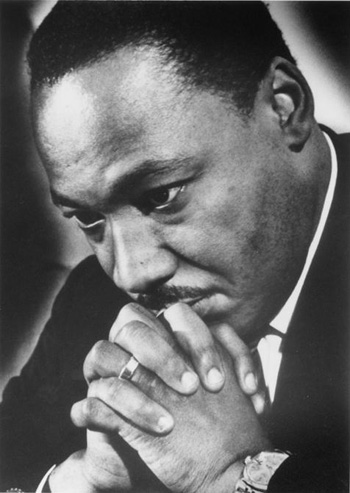

| Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in Grosse Pointe Farms, Michigan on March 14, 1968, just a few weeks before his assassination. Photo courtesy of the Pan-African News Wire. |

Later my Mexican friends and I walked near the lovely rose garden,

crossed historic Auburn Avenue, and went to the majestic marble

mausoleum where we read: “Free at last. Free at last. Thank God

Almighty. Free at last.” We stood solemnly by the eternal flame, as

though we could not move from that long moment.

The middle-aged Mexican, Job, tried to help by reminding me that

suffering does have a place and a value on Planet Earth. Finally, we

moved slowly towards the Ebenezer Baptist Church. In this sacred, red,

brick building, we watched a video of the church where Dr. King had

sung in the choir, had preached his first and his last sermon, and had

served as a world- citizen associate with his father.

We Americans need to turn in every generation towards Atlanta. We need

to drink from the water fountains with the signs that I daily saw as a

boy, but never understood: “For White Only,” or “For Colored.” We need

to feel again what it is like to ride in the back of the bus only

because of ones race. We need to touch the hardness of the steel of the

jail cell where Dr. King wrote of the strength of non-violence.

We need to remember the pain of a past plagued by prejudice. Also, we

need to make an American apology to our African American neighbors for

wrongs done, but rejoice with them in every promise of progress in our

land.

Russell B. Hilliard, Sr. is pastor emeritus of the Fountain of Life First Hispanic Baptist Church of Asheville.