Redistricting by the General Assembly: Five Legal Considerations

By Bob Joyce

By Bob Joyce

Citizens throughout the country have a right to representation in the legislative branch that is at least approximately equal. Therefore, representative districts in every state must be redrawn after each census, which according to the US Constitution must be taken every 10 years. Censuses are always conducted in years ending in “0” and the data they compile becomes available in years ending in “1.”

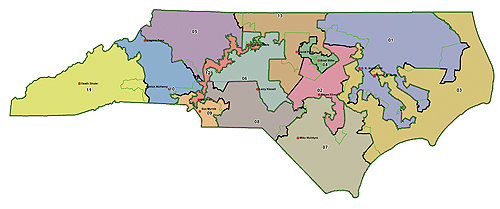

Redistricting means redrawing the districts from which public officials are elected. The General Assembly is responsible for drawing new districts for allocation of seats in the US Congress and the NC House and Senate. Many county commissioners, school board members, and city council members are elected by districts as well. Once adopted, a valid NC Senate or House redistricting plan may not be changed during that decade. If the plan is not precleared under the Voting Rights Act (discussed below) or if the courts overturn a plan, then a new plan may be adopted.

|

| Bob Joyce has practiced law with Chadbourne & Parke in New York, and with Barber & Joyce in Pittsboro, NC. |

Redistricting faces many issues of partisan politics and good

governance, but for the moment let’s focus on five legal considerations.

(As a side matter, keep in mind that, in addition to more than 100

counties, cities, and school units that elect their governing boards

from districts are now undergoing the redistricting task, and for them

the legal issues are principally the same as those facing the General

Assembly).

The first of the five is: Districts must contain about the same number

of people each. This requirement commonly goes by the name

“one-person-one-vote,” and it is a requirement that, as the US Supreme

Court has said for the past fifty years, comes directly from the US

Constitution.

There was a time when state legislatures did not try to make districts

the same size: until the 1960s each county in North Carolina was

entitled under the state Constitution to one member of the state House,

no matter how small the county’s population. But the Supreme Court said

that uneven districts violate the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment of the US Constitution, because people living in

more populous districts have votes that count less than people living in

smaller districts. So now the rule of thumb is that for state House and

Senate districts, the spread from the least populous district to the

largest, when the new districts are drawn, cannot exceed 10 percent.

And, the US Supreme Court has said, for seats in Congress the

requirement is even stricter—very little deviation is allowed.

In the last redistricting after the 2000 census, all congressional

districts were drawn to be within one person of the same size. The

one-person-one-vote requirement will be challenging to meet, but the

legal concept behind it is really straightforward.

The second of the five legal considerations is, by contrast,

complicated and subtle: The proper consideration of race in the drawing

of districts. The general legal principle is that race should not be the

dominant factor in the drawing of districts. The US Supreme Court said

exactly that in a redistricting case arising in North Carolina. Yet

there are two circumstances in which the law requires that race be taken

into account, and both of those arise under the federal Voting Rights

Act of 1965. That Act has two central provisions. Section 2 prohibits

discrimination in the administration of elections everywhere in the

country; Section 5 requires the pre-clearance of electoral changes in

some jurisdictions in the country, including 40 North Carolina counties.

The Voting Rights Act and court cases decided under it forbid drawing

districts that dilute minority voting strength. For the 40 counties in

North Carolina covered by Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, this means

avoiding “retrogression,” or worsening the position of racial

minorities with respect to the effective exercise of their voting

rights.

All 100 counties are subject to Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act,

which may require drawing districts which contain a majority minority

population if three threshold conditions are present: 1) a minority

group is large enough and lives closely enough together so that a

relatively compact district in which the group constitutes a majority

can be drawn, 2) the minority group has a history of political

cohesiveness or voting as a group, and 3) the white majority has a

history of voting as a group sufficient to allow it to usually defeat

the minority group’s preferred candidate.

The totality of circumstances, including a past history of

discrimination that continues to affect the exercise of a minority

group’s right to vote, must also be taken into consideration. These

rules come from Thornburg v. Gingles, a landmark US Supreme Court Voting

Rights Act case arising from North Carolina in the 1980s.

Under Section 2—the general anti-discrimination provision—North

Carolina has seen successful lawsuits that challenged the ways in which

certain elections were conducted, including challenges to the past ways

of drawing legislative districts. The remedies that the courts imposed

in those lawsuits required the consideration of race in the drawing of

districts, mandating the creation of districts that had a majority

African American population, again including a number of legislative

districts, to enhance the opportunities for African American voters to

participate in the electoral process and to elect candidates of their

choice. As a result, the General Assembly is obligated to continue to

consider race in the drawing of districts where those remedies for prior

discrimination have been put into place.

And under Section 5—with respect to those 40 NC counties covered by its

provisions—the law requires that electoral changes, such as redrawing

lines to meet the one-person-one-vote requirement, must not be made in

such a way as to make it harder for African American voters to

participate in the electoral process and to elect candidates of their

choice. Changes that make it harder are termed “retrogressive,” and the

US Department of Justice will not pre-clear such changes, unless perhaps

demographic shifts have made the retrogression unavoidable. The entire

state-wide plans must be submitted for pre-clearance, because every part

of a plan will depend to some extent on every other part.

The third of the five legal requirements: With respect to the state

House and Senate districts, the General Assembly must keep in mind the

“Whole Counties” provisions of the state Constitution. The Constitution

prohibits dividing counties in drawing legislative districts. In

interpreting that provision, our state Supreme Court has recognized that

the primacy of federal law means that considerations under the Voting

Rights Act, as described just above, must be met first, and they may, in

the proper circumstance, require the dividing of counties. Beyond that

consideration, however, the state Supreme Court has given a roadmap of

instructions to the legislature on how to combine counties into

groupings and then to create divisions within the groupings to meet as

fully as possible the one-person-one-vote requirements and the Whole

Counties provision at the same time.

The fourth of the five legal requirements was defined by our state

Supreme Court recently: In the drawing of maps for the state House and

Senate, the General Assembly may not use a mix of single-member and

multi-member districts. Multi-member districts were once common. The

practical consequence now is that all districts must be single-member.

The fifth of the five legal requirements is found in the state

Constitution: All state House and Senate districts must be composed of

contiguous territory.

In addition to these five legal requirements, there are three other

significant concerns. One, the US Supreme Court has been clear that

incumbency protection is a legitimate concern in drawing districts. Two,

there has long been a consensus that compactness in the drawing of

districts is a desirable consideration, even if it may not be literally

required. And three, it is highly desirable from the point of view of

elections administrators that the General Assembly not split voting

precincts in the drawing of districts. Not only is administration eased,

but the likelihood of error is reduced.

Redistricting is inherently a political exercise, but it operates within these legal constraints.

Bob Joyce joined the UNC-CH School of Government (then the Institute

of Government) in 1980. He has practiced law with Chadbourne & Parke

in New York and with Barber & Joyce in Pittsboro, NC. He is a past

member of the executive committees of the Education Law Section of the

North Carolina Bar Association and the North Carolina Council of School

Attorneys. He has served as editor of the School of Government’s

Legislative Reporting Service, School Law Bulletin, and Popular

Government.

His publications include The Law of Employment in North Carolina’s

Public Schools, The Precinct Manual, and chapters in Education Law in

North Carolina. Joyce earned a BA from the University of North Carolina

at Chapel Hill, and a JD from Harvard Law School.