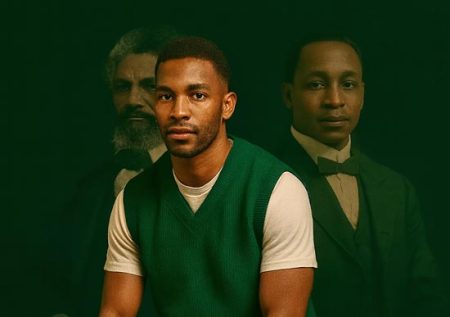

York – an Enslaved Explorer

York’s service was crucial to the success of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

The first African American man to traverse the continent.

York, born in Virginia in about 1770 was a member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. He was an enslaved man who belonged to William Clark, the expedition’s co-leader. York was born into slavery, the son of “Old York” and Rose, two enslaved laborers owned by Clark’s father John.

In Virginia, where Clark grew up, it would not have been uncommon for a White boy to have an enslaved boy as a personal servant. York fulfilled that role, and remained Clark’s servant until the late 1800s, years after the expedition ended.

When Meriwether Lewis invited Clark, his army buddy and an accomplished soldier and outdoorsman, to accompany him on a journey across the newly acquired Louisiana Purchase Territory in 1803, the two needed additional men to accompany them on what would be called the Corps of Discovery. They selected soldiers, interpreters, and French oarsmen who knew the country better than they. And they chose York, Clark’s 6-feet, 200-pound Black, enslaved, personal servant.

When the expedition began in 1804, not all of its members—White men raised in the South— were eager to have an African American at their side. About a month in to their journey, one of the members threw sand at York, which according to Clark’s journal, resulted in him nearly loosing an eye. But, for all intents and purposes, York’s role in the Corps of Discovery was equal to that of the expedition’s White men. During the expedition York regularly managed to shoot buffalo, deer, and geese to feed the members of the party.

A combination of fear and curiosity about York may have given Lewis and Clark a leg up in their interactions with Indigenous people. Clark often chose York to accompany him on scouting trips and, when game was scarce later in the journey, York was sent with one other man to barter for food with the Nez Perce.

York was a fascinating sight to the Nez Perce. In his journal, Clark wrote about the men inspecting York and rubbing his skin with sand to see if he was painted. They called him ‘Raven’s Son’ for his color and the ‘mystery’ he embodied. The Arikara people of North Dakota referred to York as “Big Medicine” and speculated that he had spiritual powers.

York’s service was crucial to the expedition’s success. According to The Journals of Lewis and Clark, during the expedition, York was entrusted with a musket, killed game, and helped to navigate trails and waterways. Despite his contributions to the Corps of Discovery, Clark refused to release York from bondage upon returning east.

After their return to St. Louis, sometime in 1809, York expected to be given his freedom after the successful expedition was over. York, who was married and had a family before beginning the expedition, requested to be returned to Kentucky from Clark’s home in Missouri to be with his wife. Clark complained about York’s behavior and punished him by hiring him out for at least a year to a Louisville, Kentucky, farm owner who was known for physically abusing his enslaved laborers. By 1811, York’s wife was gone from the area: her owner had moved to Mississippi, taking her with him.

Clark’s grandson, in a memoir, mentioned that York was Clark’s servant as late as 1819, some 13 years after the expedition returned. Some 20 years later, in an 1832 interview with author Washington Irving, Clark claimed that he freed a number of his slaves, including York. Historians, however, have noted that there are no documents establishing that Clark ever freed York.

At some point York did gain his freedom, although Clark insisted that York hated freedom. According to him, York tried to found a cargo company, failed because of poor discipline and decided to return to Clark and to slavery, only to die of cholera on the way to St. Louis. According to historians, Clark’s story reflects pro-slavery arguments that African Americans were happy to be enslaved, and could not lead successful lives as free people.

There is no clear record of what happened to York. In 1839, Zenas Leonard, a fur trader who published a highly reliable memoir of his travels throughout the West, reported meeting “a Negro man” living well among the Indigenous peoples we know as the Crow in what is today north-central Wyoming. The Black man said he had returned to the area from St. Louis after first visiting the area with Lewis and Clark.

What is known is that York was a courageous, ingenious, brave, and self-sacrificing Black hero who was able to overcome all of the obstacles that slavery and a hostile frontier threw at him.