Buncombe County and Redistricting

|

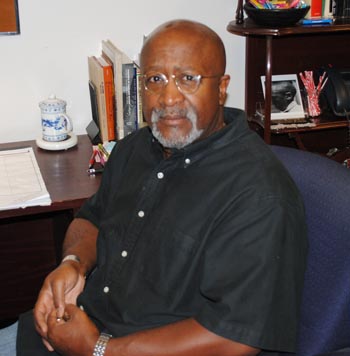

| Dr. Dwight Mullen is a professor of Political Science at UNC Asheville. Photo: Urban News |

by Johnnie Grant

Not since the 1800s has the Republican Party had control of both chambers of the North Carolina legislature and, thus, control of redistricting. The party’s redistricting map make four US Congressional seats harder for Democratic incumbents to hold. Reps. Mike McIntyre (D-7th District), Larry Kissell (NC-8), Heath Shuler (NC-11), and Brad Miller (NC-13) will all be fighting for their political lives in 2012.

Dr. Dwight Mullen is a professor of Political Science at UNC Asheville. We asked him to comment on the redistricting plan passed by the legislature this summer.

“From a scholarly standpoint I look at things historically,” said Mullen. “Historically this fits the position the Republican Party has taken with regard to populated urban areas, and areas significantly populated with African Americans. This redistricting process was done to break the democratic hold on the 11th District.”

We asked him how map-drawing allows a party to strengthen its hold or weaken the opposition.

“[They] looked at the Democratic stronghold districts within the state

of North Carolina and where the lines are currently drawn, and

reconfigured them. The goal is to concentrate a party’s own voters into

districts the party has newly won.” Alternately, a party can move voters

of the opposing party out of an existing Republican district and into a

new district, “to strengthen your party’s chances in the old

districts.”

It is a tedious and often litigious process that follows the 10-year

census cycle. “It’s a numbers game and strategy,” said Mullen, “and the

hope is that the voting public will be oblivious to what is happening.”

How will the new maps impact Western North Carolina and Asheville, the

city at its heart, which together have comprised the 11th Congressional

District since its inception.

Mullen noted, “Residents within the City of Asheville normally vote

Democratic. What the redistricting does (even though nothing has been

finalized) is to dilute that vote, if nothing else. If you look at

Buncombe County, it looks as though a bubble was drawn around the center

city of Asheville. These new lines include Asheville voters within the

10th district, which starts in the Piedmont,” explained Mullen. “[It’s]

represented by Patrick McHenry of Gaston County, one of 40 counties in

North Carolina under federal mandatory preclearence.”

Preclearance is a requirement that any redistricting that substantially

changes the impact of the votes of minorities must be precleared by the

Justice Department. The counties under preclearance requirements had

historically shown unequal treatment of black voters, and under the

Voting Rights Act their actions are still subject to scrutiny. Buncombe

County doesn’t have preclearence so, in Mullen’s words, “it’s an easy

target.”

State Republicans defend their redistricting efforts, suggesting that

the state’s booming population and a surge in Republican voters makes

redistricting necessary. But they have difficulty explaining why the

center of the district should be removed from it.

“The 10th district snakes up the interstate to include Ashevilleans in a

district they’ve never been in before, and represented by someone they

don’t even know. Nobody really knows Patrick McHenry here in Asheville,”

said Mullen. “It looks quite odd and deliberate.”

“The wild card in this process is the Voting Rights Act”—and whether,

and how, “the US Department of Justice enforces it,” concluded Mullen.