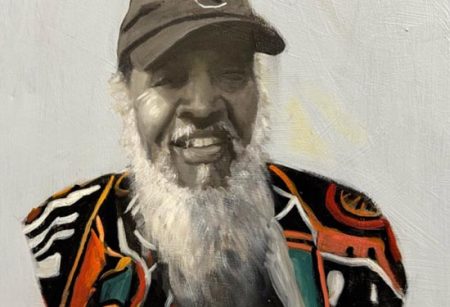

Isaac Coleman Remembered

On Tuesday, May 10, western North Carolina lost one of its most valued civil rights activists and community leaders, when Isaac Coleman lost a brief, intense battle with cancer at the age of 72.

He died at Novant Health Presbyterian Medical Center in Charlotte; he is survived by his wife, Wanda Coleman, and nine sons and daughters.

Coleman was a soft-spoken activist who showed up everywhere where work was to be done—canvassing for city council candidates, speaking out on political issues, strategizing over dinner on African American and Latino unity, or cooperating quietly with others to establish such essential organizations as Just Economics and Read To Succeed.

His activism began early, when he was a 17-year-old student at Knoxville College, a small African American college in Tennessee, participating in sit-ins aimed at integrating public accommodations. “I was in jail practically every other day,” he told The Urban News in 2006. “We college students created such an uproar in Knoxville that the city officials negotiated with the college officials to try to make us stop demonstrating. They threatened us with expulsion, and a lot of the group dropped out at that point.”

Rather than dropping out, Coleman and others prepared to picket the ceremony at which Knoxville was supposed to receive an “All-American City” award. But before the event, the police were waiting, and a judge sent them to jail for 30 days. He then returned to college, but never stopped serving the community.

In 1964, shortly after the murders of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner during “Freedom Summer,” Coleman went to Mississippi at the urging of future Washington, DC Mayor Marion Barry, then a student at the University of Tennessee. He signed on with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) to work on voter registration projects as well as a “Freedom School” that included tutoring and a library for youth. He then went to Tupelo as project director of a campaign to elect one of Medgar Evers’s brothers for governor.

“We were working in the housing projects,” he said. “The police started coming after us so we skipped town.” He rode with other civil rights workers, a white man and two white women, sitting in the back seat next to a white woman. “We got arrested in the next town. When the cop looked into the car and saw me there, he grinned and said, “Nigger, you’re in big trouble!”

By 1971, after years of struggle, having his Tupelo home firebombed, and meeting and working with Fannie Lou Hamer and other movement leaders as a member of the Mississippi Freedom Party, Coleman was ready to leave Mississippi. In Asheville he met the late Carl Johnson, the “Mayor of Hillcrest” who had organized the housing community’s rent strike in 1968.

“My first impression of Asheville was when I rode into the city (in 1971) and saw these houses hanging off the side of the mountain,” he said describing the East End community along Valley Street before it was destroyed by urban renewal. Housing had long been a concern for Coleman, and in Asheville he worked first for Model Cities, then for twenty-seven years as a city housing inspector, and later for the Housing Authority as manager of Deaverview Apartments.

During those years he was active as always, both in politics and civic life. He was an originator of such programs as the Kindness Campaign, designed to “spread the philosophy of kindness in the social, economic, and political spheres,” including a Kind & Safe Schools program to help relieve tension between socio-economic and racial groups by decreasing bullying and heading off gang activity.

Coleman also cofounded the African-American-Latino Coalition, known as “Afro-Tina,” about which he said, “Many of the problems that Latinos face are similar to those of African Americans. We need cultural understanding between the two groups… We need to unite to overcome the socio-economic barriers both groups face.”

In January 2005, he became involved with the Progressive Asheville Coalition to elect progressives to City Council. He volunteered with campaign committees for Robin Cape and Holly Jones and ran the successful campaign in which Terry Bellamy became Asheville’s first African American mayor. Later he served as Vice-Chairman of the Buncombe County Democratic Party and as a member of the NC Democratic Party’s executive committee, offering advice, mentorship, and volunteer help to many other candidates, including newly elected Asheville City Councilman Keith Young.

Coleman was a cofounder of Just Economics, which has become a national model for analyzing the cost of living, wages, and how they affect a community; and Read To Succeed, which grew out of his involvement with helping increase opportunities for the many children in poverty who live in public housing.

Over the years Coleman was recognized for his community service and work by numerous organizations, including Awards for Service from the City of Asheville and the Housing Authority of the City of Asheville, the Martin Luther King, Jr. Arc of Justice Award, and the Asheville City School Foundation’s Champion Award. But his greatest legacy will be the organizations that will continue to carry on his life’s work as a patriot and leader, and to which he dedicated himself for more than half a century: greater liberty and greater justice for all people.