Jason Johnson’s Soul Sanctuary

by Bill Moore

On Display at the YMI Cultural Center

The first thing you notice about the photographs is the intensity of the moment.

From the congregation to the choir, all is motion and emotion. The author/photographer of Soul Sanctuary, Jason Miccolo Johnson spent ten years crossing the country and documenting both the uniqueness and transcendent joy of the “black church.” The photographs currently on view at the YMI Cultural Center capture a sense of that joy and vitality in the worship services, baptisms, singing, and preaching.

|

| Jason Miccolo Johnson will be present for the formal opening of “Soul Sanctuary” January 25. |

It’s easy to become caught up vicariously in the energy

these photographs convey. In the stark emptiness of the gallery, the

pictures, like the people in them, quietly demand your attention. The

photographs also speak about a sense of worship and spirituality that

doesn’t depart when you walk out the doors of the sanctuary. You have

been strengthened, as Johnson was quoted as saying in the Philadelphia

Daily News, to “tell the truth, live by example, walk by faith, but run

when you have to.”

There is a political message as well in these pictures. The church as a

unifying and protecting force, even through the dark days of oppression

and conflict of the Civil Rights movement, has never changed. Although

the sanctuary, even of a church, could not prevent people from being

cut down by bullets, the sanctuary that was the congregants themselves

endured. With a keen but respectful eye Mr. Johnson has captured the

strength of that endurance in the images of firey preachers, the

comforting presence of the “mothers” of the church, and the many faces

of faith, joy, and sin revealed and defeated.

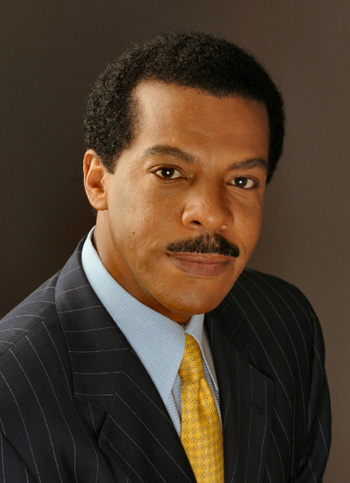

Jason Johnson was born in Memphis and grew up attending the Mt. Zion

Missionary Baptist Church, the inspiration for Soul Sanctuary. He is

the author of 15 other books including Songs of My People, Standing in

the Need of Prayer, Q: The Autobiography of Quincy Jones, Black

Mothers: Songs of Praise and Celebration, and Committed to the Image.

His work has also appeared in two major exhibitions at the Smithsonian

Institution, “Reflections in Black” and “Speak to My Heart,” and is in

the permanent collections of the St. Louis Art Museum and the Museum of

Fine Arts in Houston.

Mr. Johnson is a former photo editor at USA Today and production

assistant at Good Morning America on ABC Television. For the past 25

years he has been the official photographer for the African Methodist

Episcopal Church and since 1990 of the National Association of Black

Journalists.

The Urban News recently interviewed the author.

Urban News (UN): Was it difficult, as an photographer and journalist,

to maintain a certain detachment, or was it even necessary as you took

the pictures?

Jason Miccolo Johnson (JMJ): It was a little difficult not to be caught

up, but I was also concerned with the changing focus of the service I

tried to see it from about six different viewpoints, all sides of the

sanctuary; the “spectators” in the balcony to the very active first

five pews.

|

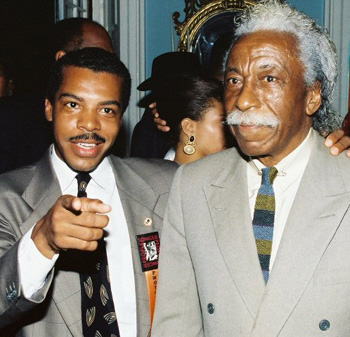

| Jason Miccolo Johnson with Gordon Parks, Jr. |

UN: The pictures themselves are so evocative. Are they, in any sense, allegorical or symbolic?

JMJ: There was no overt effort to make the pictures symbolic. They are

a hundred and fifty iconic images remembered from my childhood. I

returned to that part of my childhood with “renewed eyes.” It is the

church which sustained the African American community in hard times. It

is a universal worship experience which crosses all denominational

lines.

UN: Gordon Parks says, or at least implies, in his introduction to Soul

Sanctuary, that the experience in the black church is the same whether

in Kansas, Memphis or Washington, D.C. Would you agree?

JMJ: Yes. Certainly the “black skulls being baptized” evokes the old

style of baptism as contrasted with new styles and also contrast the

rural with the urban and suburban worship. But I tried to capture the

similarity.

UN: The Memphis Commercial Appeal talks about the “mothers of the

church,” and it seems women play a much broader role in the church

congregations you photographed as spiritual leaders. True?

JMJ: Women represent about seventy-five percent of black congregations,

so yes, women do play an important role in the church, but it has not

been until recent times that they have come to the pulpit.

Traditionally, women of the church have functioned as wise counselors

and “senior mothers.” They represent not only wisdom but comfort and

care.

The church represents a sense of family which has sustained African

Americans even through the most difficult times of the civil rights

movement. Some of these pictures were taken in the AME Church in Selma,

Alabama and in Mason Temple in Memphis where Dr. King preached before

he was shot.

UN: It seems, in many of your photographs that you invoke things in threes. Was this a reference to the Trinity?

JMJ: There was no overt effort to evoke that, but the ideas of truth,

living by example, and walking by faith as well as the services’

preparation, inspiration, and call and response are part of a trilogy.

UN: When did you discover photography as an artistic medium, and what

part did Gordon Parks play in your decision to become a photographer?

JMJ: I took my first journalism course in the ninth grade. I wrote

pieces for the school newspaper, and one Christmas I received a

Polaroid camera. In the tenth grade I got my first 35-millimeter camera

and was still working on the school newspaper. This is really where it

all started. Then, when I read about Gordon Parks as a student, it

provided me with a sense of what was possible.

As far as Gordon Parks, he was my inspiration and later became my

mentor. I was chosen to organize his ninetieth birthday celebration. I

was also with him in one of the last pictures taken before he passed

away. The party was a surprise and he just lit up when he realized what

was happening. The lasting image of Gordon Parks, for me, will always

be him with arms out stretched and looking up to heaven.

UN: One final question. What is the one thing you hope people would derive from seeing and reading Soul Sanctuary?

JMJ: I hope people who see this book will come away with a greater

appreciation of the gift of observation as only still photography can

do — much better than video or movies.

The Soul Sanctuary photographic exhibit is open every day except Monday

at the YMI Cultural Center at 39 S. Market Street. Gallery hours are

Tuesday-Friday, 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.; Saturday 11:00 a.m. to 3:00

p.m.; and Sunday 2:00 p.m. to 5:00 p.m. Copies of the book, Soul

Sanctuary, are on sale at the gallery.

Jason Miccolo Johnson will be present for the formal opening of the exhibit on January 25, 2008.

For more information on this and other events contact the YMI Cultural

Center at (828) 252-4614 or visit the YMI web site at www.ymicc.org.