City, County Establish African American Heritage Commission

On January 14, 2014, Asheville City Council voted unanimously to establish an African American Heritage Commission.

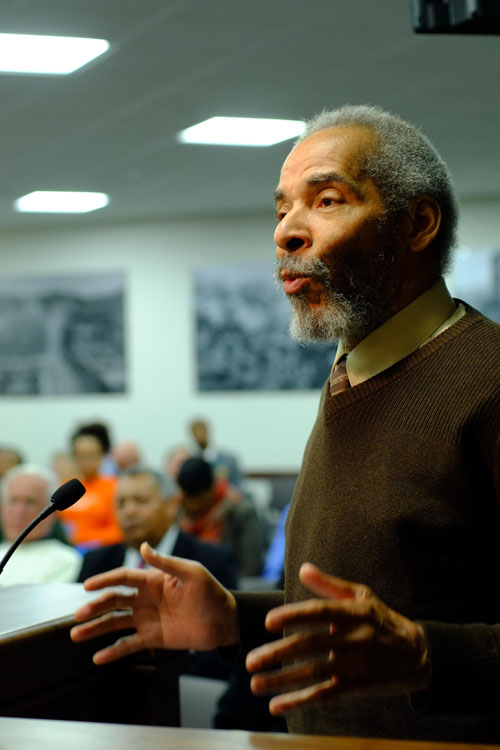

The Council acted after presentations by several residents who have worked for three years or more on planning for such a commission, to be jointly sponsored by the city and Buncombe County. Among those speaking on behalf of the idea were Marvin Chambers, Deidre Wiggins, James Lee, Dr. Lamar Hylton, Maceo Keeling, Carmen Ramos-Kennedy, Richard Graham, and CiCi Weston.

Three weeks later, on February 4, the Buncombe County Board of Commissioners followed suit, also with a unanimous vote.

Marvin Chambers, a 72-year-old Asheville native who pushed to establish the commission, stated, “Growing up, I never had the opportunity to know a lot about our (local) African American heritage except what was passed down through word of mouth.”

He mentioned some of the historic leaders of the area’s black community and added, “But very few people know what has happened here, from the days when Asheville was a road to Tennessee from SC, then a place where black folk were sold on the [steps of the] County Courthouse. It’s important for all of us to find out exactly what has been contributed by the African American community.”

Long time coming

The proposal for a heritage Commission has been a long time coming. Numerous organizations and individuals have worked over many years to bring the narrative of the African American community to light. Chambers mentioned the late Harry Harrison at the YMI, Jesse Ray’s bus tours, and classes led by Dr. Ken Betsalel, among others.

More recently, the impetus stems from the 2006 discovery of photos, taken by Andrea Clark of the East End Neighborhood in the early 1960s to mid-1970s, just prior to the coming of Urban Renewal. Clark’s photographs, made public in a book, Twilight of a Neighborhood, became the basis of an educational project about the importance of a community’s social fabric.

Developed in collaboration with the Buncombe County Library system, the project included a lecture by Dr. Mindy Fullilove at UNC Asheville in 2008, at which she shared research from her book Root Shock: How Tearing up City Neighborhoods Hurts America and What We Can Do About It. As she said, such “root shock” brings with it special disastrous consequences for both the aged and the young.

Once the exhibit and program were over, Dr. Fullilove encouraged the committee not merely to document the loss but also to work to rebuild the social fabric of the communities impacted by Urban Renewal. At her encouragement, the committee raised funds and invited authors to contribute to a special edition of Crossroads from the NC Humanities Council. Both Dr. Fullillove and Harlan Gradin of the Humanities Council felt that Asheville has a unique story and that, because so many tourists visit each year, the community’s stories could be told in a way that promote physical, emotional, and economic well-being.

At a 2010 City Council meeting, then-Mayor Terry Bellamy stressed the need for a commission by encouraging the committee to continue in their work and turn to City council for support. And three years later, on Jan. 14, business consultant Maceo Keeling said, “I am a transplant from Los Angeles, and I scrutinized our nation for a place to retire before choosing Asheville. Then, when I arrived here, I was woefully distressed by invisibility of the African American community, both professional and general. But since coming here I have had occasion to work with many individuals and business owners, and there is such a need for this commission.”

His enthusiasm was echoed by CiCi Weston, an Asheville native and member of the Executive Committee of the NAACP Asheville Branch. “Our youth don’t know much about our heritage, and as a result we don’t see many of our young professionals return to Asheville. They go to college to get advanced degrees, and they don’t come back. If we want to bring young black professionals back to Asheville once they leave, they need an inclusive community to come back to.”

What are the goals of the Heritage Commission?

Since the beginning of non-indigenous settlement in the 1780s, the African American community has been part of the Asheville region. Yet there is very little recognition or comprehensive documentation of their contributions. For most of that time, since the first census in 1800, Asheville’s African American population has hovered around an average of 14%. Still, most of these stories are audible only for those now living who experienced them, lacking a stable testimonial that can resonate throughout history.

The goals of the Heritage project are to discover, develop, promote, and implement projects and programs to recognize African American history in Buncombe County. So the initiative, according to organizers, is about “our shared history.”

While it is hard for many native blacks to face, Pack Square is part of that shared history, one whose story is rarely publicly discussed but stands as a powerful example of what is lacking in many of the stories we tell about ourselves. While there are three markers commemorating soldiers of the Confederacy at Pack Square, nothing there commemorates that the square is also the site where slaves were sold on the Courthouse steps, where slave deeds (recently unearthed), were recorded, and where punishments took place. And within the memory of many people alive today, it was also the site of public bathrooms—for whites only.

Why a Commission is needed

This initiative is about a sense of belonging, and pride of place. “After hearing disparaging remarks and comedy ‘satire’ being made by tour guides along the Eagle-Market Street area known as ‘the Block,’ I was devastated and disheartened,” said Johnnie Grant, describing experiences that took place during a salon visit and after a dinner with visiting guests. “People on the tours (both times) were laughing at what was being said, and my out-of-town dinner guest stood there in shock and disbelief!”

Grant, an East End native and innovator of the African American Heritage Commission’s planning and development, said, “I knew that moment it was time to move forward with a plan to give credibility and enlightenment about local African Americans and institutions that helped Asheville become what it is today. This is for people who visit, come to live here, and for the children and young adults.”

And, she added, “Of course, the African American Heritage Commission will also strengthen economic development. With an annual tourism base of nine million people, if even a small fraction of those folks stay one more day to learn about the area’s African American heritage, there will be a measurable economic impact.

“Charlotte, Wilmington, Charleston, Savannah, and Birmingham, among other cities, have created jobs through the development of strong story-telling and tourism centers. Putting ‘more heads in beds’ by raising the profile of historic sites and tours that tell stories like that of ASCORE have great potential for generating tourism growth,” concluded Grant.

Reclaiming a community, its people and institutions

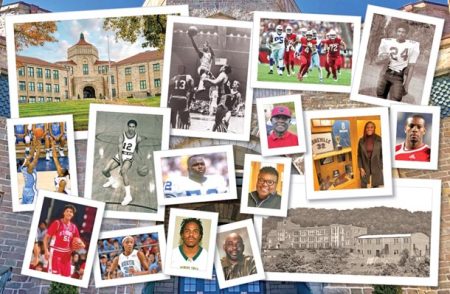

Many institutions and neighborhoods are etched in Buncombe County history, including East End, Southside, Burton Street, Stumptown, Shiloh, the YMI, Stephens-Lee High School, the Allen School, and numerous historic churches and sites.

There are also the stories of educators, professionals, and entrepreneurs including Lucy S. Herring, Isaac Dickson, E.W. Pearson, Edward Stephens, Hester Lee, Dr. John Holt, James Vester Miller, Ruben Dailey, Floyd McKissick, James “Bo” Ferguson, and many others. With the increasing push of gentrification, stories of survival and triumph in historic neighborhoods (some dating to the early 1800s) will soon be forgotten.

Students also thirst for a larger sense of the community and themselves. They need a way to learn to see the mountains and think not only of a geography but also of a people and place. They need to learn such stories as the Asheville Student Committee on Racial Equality, ASCORE, a group of teenagers who worked to desegregate Asheville institutions such as libraries, restaurants, buses, swimming pools, and parks.

Ultimately, looking back to the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries helps prepare the community for the 21st century and an economy that values diversity. As the world gets smaller and more diverse, the importance of ‘cultural competency’ and diversity in the workforce grows. Learning about Black Mountain’s Carver School, the region’s Rosenwald Schools, the historic YMI, Allen School, Appalachian African Americans and the renewed Reid Center will both broaden and strengthen the community’s self-understanding and demonstrate Asheville’s commitment to meeting the diversity challenges of the 21st century.

Collaboration the key

The Commission is to be a collaborative effort, rather than a new organization, that will harness the power of non-profits, neighborhoods, individuals, educational, and governmental agencies to talk about the black community’s shared history.

As newly elected Mayor Esther Manheimer noted, “There are lots of functions of this commission that some of us envision. We have also discussed the hope that this commission might be able to be a sounding board for projects and planning that might be discussed for African American communities. The city is trying to put together a lot of enhancement projects in infrastructure and development in historically African American communities, and this is a great way to engage the community.”

Among the other community members behind the proposal were: Father Jim Abbott, Rob Amberg, DeWayne Barton, Marilyn Bass, Ken Betsalel, Andrea Clark, Isaac Coleman, Marvin Chambers, Harlan Gradin, Johnnie Grant, Pat Griffin, Robert Hardy, Harry Harrison (deceased), Sarah Judson, James Lee, Karen Loughmiller, Bruce Kennedy, Carmen Ramos-Kennedy, Benny Lake (deceased), Deborah Miles, Dwight Mullen, Betsy Murray, Priscilla Ndaije, Henry Robinson, Deidre Wiggins, and Sarah Williams.

Organizations in support of the proposal included the YMI Cultural Center, the Anderson-Rosenwald School Restoration Committee, the Center for Diversity Education, the NAACP-Asheville Branch, and the WNC Historical Association and Asheville Chamber of Commerce.