Serving the Community with Honor, Integrity, Equality, and Fairness

|

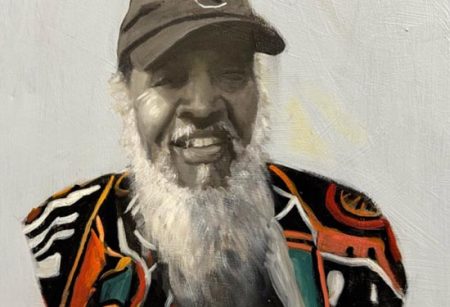

| Asheville’s new Police Chief, William J. Anderson. Photo: Renato Rotolo |

Staff reports

The Urban News met with William J. Anderson recently so that we could get to know Asheville’s newly appointed Chief of Police—and help our readers do so as well.

The Asheville Police Department has been roiled in the past year by an evidence-room scandal and by complaints of unfair treatment. The release last fall of two local men, both black, who had served more than 10 years in prison for a crime they did not commit, only heightened the community’s perception of the police, the sheriff’s department, and the district attorney’s office as biased.

That perception is only intensified by the refusal of some law

enforcement professionals to acknowledge such mistakes, even in the face

of clear, overwhelming evidence.

Some residents, in fact, view the police as an enemy rather than an ally in keeping Asheville safe and equitable.

Many citizens are hoping that having an African American lead the

Asheville Police Department for the first time in its history might help

restore trust between the community and the department. How, then,

would Chief Anderson go about establishing better relationships with the

community at large? How does he plan to rebuild the image—and the

reality—of who the police are in the eyes of the city’s residents?

The chief acknowledges that as a newcomer to Asheville, it will be

essential that he meet with area residents to find out what’s going

on—from their perspective.

“We need first-hand knowledge, so we have to ask questions,” he said.

“We have to learn what has worked, or has not worked in the past. And a

lot of what we do will be based on my past experience. I’ve been in this

business a long time, and have a lot of experience to bring to the

table. However,” he adds, “my advice to drug dealers, and my message to

them, is—‘We’re coming.’”

|

| William J. Anderson. Photo: Renato Rotolo |

He continued, “I plan to be as visible and as interactive as possible,

especially with those communities where there may be problems. I plan to

listen to all communities, not just the ‘problem areas’ but

everywhere.”

Another approach that Anderson discussed is that of deterrence and

rehabilitation for problem youth and unlawful offenders. “Deterrence is a

big part of what we have to do,” said Anderson.

The chief described a program established in Greenville, NC, (his

previous post) called the Pitt County Reentry program, and his active

roll in the inception of the High Point Focus Deterrence Model. Both

programs offered supportive resources from the community at large: help

with jobs and housing, stability, and an educational component.

“A person has to make a conscious decision that they’re not going to

violate the law, and that they want to make a change. We present them

with the options and the resources, but they have to make the choice,”

Chief Anderson said.

He also pointed out that it made a difference that the police

department did not act alone, and the business community played a big

role, as did community organizations.

When The Urban News asked about the potential participation of such

stakeholders as CIBO (Coalition of Asheville Businesses), the Downtown

Business Association, clergy, A-B Tech, the Chamber of Commerce, the

Dept. of Corrections, Western Carolinians for Criminal Justice, ACLU,

and others, he noted, “We did sit around a table, talked about the

problems we faced, what direction we should take, and what we were able

to do. When we reached a consensus, we wrote a grant [to implement

programs].”

The Urban News publisher Johnnie Grant raised the question of perceived

harassment by a local citizen. “We (The Urban News) often receive phone

calls from local citizens who [say they] have been harassed by law

enforcement. One caller described himself as a professional can

recycler, and claimed can-recycling as his way of earning a living. He

stated where he has permission to collect cans for recycling, he was

cited by law enforcement for trespassing. On one occasion, he told us,

his bags full of cans were seized and rummaged through by the police. He

was then issued a citation for having open beer containers, because

some of the cans were not completely emptied. He has been stopped by law

enforcement countless times, and had to appear in court—wasting the

court’s time and his limited monetary resources. Those types of actions

by law enforcement spread quickly throughout the community as police

harassment.”

|

| William J. Anderson. Photo: Renato Rotolo |

Chief Anderson immediately invited The Urban News to put the man in

touch with his office. “I think the first thing is, he needs to come

talk to me, and tell me his side of the story. Let me research it, and

find out what’s been going on. Sometimes policies can change, procedures

can change. But first let’s sit down and talk about it.”

He noted that after getting the citizen’s story first-hand, he would

then dig into department records to determine, “Why has this man been

stopped, how many times, and what is making this happen? Maybe we can

change things that we’re doing, maybe he can change some things that

he’s doing.”

Chief Anderson asserted, “I want to see for myself. And I’ll be looking

elsewhere, and all over the city. You may see me in various community

areas observing, accessing, and gathering information for myself.”

“My history has been to have working relationships with all the

communities that we as law enforcement serve. I hope to see some of the

same results here. But change doesn’t happen overnight. It will take a

lot of work on my part to be visible out in the community over time, and

to see some of the things that are happening, to discuss it in the

department, develop training, change perspectives, and so forth. First

we have to identify issues, then take steps to correct them,” said Chief

Anderson. “The only thing I can do is my job. I can only control what I

feel is right and in the best interests of the community and this

department. I don’t play politics; I can be conscious of the dynamics,

but I can only do what is lawful, moral, right, and let the chips fall

where they may.”

Anderson expressed sympathy for those who are—or perceive that they

are—treated differently on account of race or ethnicity, including many

in the Latino community. Anderson was part of a broad-based Latino

initiative out of Raleigh that gathered community leaders to visit

Mexico to try to understand what lies behind the emigration phenomenon.

The initiative traveled to Veracruz to learn why so many people from

that region in particular come to North Carolina. More recently, he

attended a presentation by an Asheville Police Department officer about

having a Hispanic/Latino liaison in the APD. “When this officer made the

presentation here, I was very impressed,” he said.

He also had kind words for the Citizens Police Advisory Committee, with

whom he met during his first week in office. “I will be meeting with

them again soon. They are very active and very involved. And we’ll be

meeting next about specific goals and objectives that we can

accomplish.”

Asheville’s first African American chief of police acknowledged that he

arrives with high expectations from the community: expectations both of

his performance as chief, and in rebuilding the long-fractured

relationships between his department and the community.

The impression Chief Anderson made upon The Urban News staff was that

of a cool, calm professional who will not bend the rules for anyone, but

will apply the law as it is written, and try to do so equitably and

fairly.

Whether equitable treatment is perceived as such by the affected

communities remains an open question for the moment. But as a capsule

portrait, anyone over 50 who meets him will be reminded of Sgt. Joe

Friday, interested in “just the facts, ma’am”; younger residents can

only hope that he is able to meet those high expectations.