What is Needed to Improve the Life of Seniors in the Asheville Buncombe Community?

Only You Can Tell

By Elizabeth Russell

In his article “Racial Segregation and Longevity among African-Americans: An Individual-Level Analysis,” Thomas A. LaVeist set out to test the relationship between racial segregation and mortality using a multidimensional questionnaire-based measure of exposure to segregation. He notes: “At the beginning of the century, average life expectancy in the United States was 47 years old. By century’s end, life expectancy had risen to excess of 70 years, and it was not unusual for Americans to exceed 80 years of age.” However, he continues, “African-American life expectancy at birth is persistently five to seven years lower than whites.”

Data for this analysis comes from the National Survey of

Black Americans (NSBA), a national multistage probability sample of

2,107 African-Americans aged 18 to 101. The household survey was

matched with the National Death Index (NDI), and the principal findings

offer no surprises. Respondents who were exposed to racial segregation

at home and at work were significantly less likely to survive the study

period after controls for age, health status, and other predictors of

mortality. LaVeist’s conclusion: The results support previous studies

linking segregation with poor health outcomes.

|

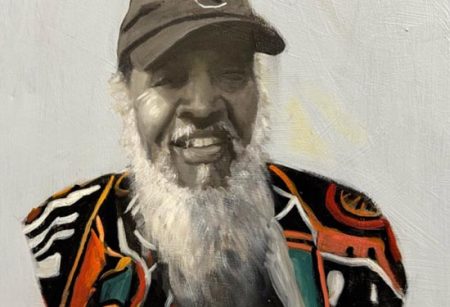

| Pictured are senior citizens who visit the Senior Opportunity Center in Asheville, saying they find comfort in sharing and helping each other. Front row (from left to right): Mary Briscoe, Johnnie McCorkle, Geneva Fate, Lillie Carson, Hattie Carson. Middle row: Lucille Smith, Gaynell Galloway, Spark Haynes, Ivan Donaldson, Alvin Fate, Frances Water. Back row: Steve Watson, and Barbara Young. |

LaVeist’s work has informed Asheville’s Mount Zion Community

Development (MZCD) project NAAF (Nurturing Asheville Area Families),

which strives to reduce the relatively high rate of mortality among

area African-Americans. MZCD has also instituted a teen pregnancy

prevention program that through education and opportunity helps teens

to see the bright horizon beyond high school.

As every adult knows all too well, the choices made during teen years

often determine future personal and family growth and achievement.

These programs have been followed by other efforts at bringing about

greater equality of opportunity for all ages in the African-American

community.

Recently the Asheville Buncombe Institute of Parity Achievement (ABIPA)

has assumed leadership in narrowing gaps in service access for health

care and economic opportunity for African-Americans living in the area.

ABIPA, through the PACD program, proposes to close the gaps through its

Parity Action Teams (PAT), which concentrate on providing support for

individuals in need. Volunteers offer help in Basic Life Skills,

Education, Employment, Housing, House Maintenance, Health Management,

Nutrition, Meals, Self Employment, Transportation, and Telephone

Support. ABIPA also offers an array of News Highlights for health every

month.

November Programs

Body & Soul: A Celebration of Healthy Eating and Living. A health

program developed for the African-American church, presented jointly

with The American Cancer Society on November 8 from 1-3 p.m. at St.

James AME, 44 Hildebrand Street.

On Saturday, November 10, beginning at 3:00 p.m. at Mount Zion, 47

Eagle Street, seniors will be asked questions that define their quality

of life. And on November 15 from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m., the North Carolina

Center for Creative Retirement and UNC Asheville’s Health &

Wellness Department will host a wellness fair for all adults at the

Reuter Center at UNCA. Among other benefits to participants, students

enrolled in AB Tech’s Massage Program will offer free chair massages,

and healthy and nutritious food will be provided.

Successful Aging

At the 2004 Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association

Preliminary Program, presenters Mary E. Byrnes and Heather Elise

Dillaway of Wayne State University examined recent literature on

“successful” aging. The literature on successful aging suggests that

older adults who remain free from disability will maintain a high level

of physical and cognitive functioning, continue interpersonal

relationships, and contribute productively to society.

But much of the research and resultant literature on successful aging

has been quantitative, defining “aging” as well as “success” in aging

very narrowly. What’s needed, according to Byrnes and Dillaway, is more

qualitative research and a broader conceptualization of what it means

to age “successfully,” so as to promote a greater understanding of how

diverse populations conceptualize and engage in aging processes.

Also at the 2004 conference, Vallarie Henderson of the University of

Cincinnati addressed the question, “Do African-Americans Hold the Key

to Longevity?” She presented demographic research on mortality showing

that people in lower socioeconomic strata die sooner than their

wealthier counterparts. But while African-Americans have higher death

rates than whites in the earlier and middle years of life, those rates

eventually reverse.

Henderson argues that some sociological factors could have a positive

impact on the health and mortality of African-Americans. For example,

far fewer elderly African-Americans than whites live in nursing homes,

and the social support received from family and the often negative

effect of living in a nursing home could help explain the difference.

LaVeist writes, “The ways in which whites and African-Americans

experience American society can differ greatly. Also, with the

expansion of educational, housing, and occupational opportunities for

African-Americans that has occurred over the past four decades, there

is now significant variation in the ways in which African-Americans

“experience” America.”

He belives that “it is not segregation in itself

that is predictive of health outcomes. Rather, segregation is

reflective of race differences in the social infrastructure, material

living conditions, and life chances of whites and African-Americans. A

consequence of these ‘different Americas’ is that different race groups

have different levels of exposure to health risks. These different

exposures can be environmental, socioeconomic, or political.”

Among the differences LaVeist cites are:

• Liquor stores in Baltimore, MD were eight times more likely to be

located in a low-income African-American community compared with other

communities.

• African-American communities have greater exposure to environmental hazards.

• Grocery and other food service stores were less available in minority communities.

• Certain pharmaceuticals were unavailable in segregated African-American and Latino neighborhoods in New York.

But middle-class, racially segregated African-American communities in

and around such cities as Atlanta, Baltimore, Birmingham, Chicago,

Nashville, and Washington, have avoided the social problems typically

associated with segregated African-American areas. Upper-income

racially segregated communities may have a more beneficial set of

characteristics, and possibly better health outcomes, than poorer

communities.

Moreover, while most of the consequences of segregation are negative,

there are some known benefits of segregation. Researchers have found

that in racially segregated cities African-Americans develop more

political empowerment, establish more community cohesion, and like

other ethnic groups have been able to develop a self-supporting

business class.

The segregation/health relationship has not yet been examined within

the context of a race/class interaction. Studies to date have serious

limitations, as outlined by LaVeist. But, he also writes, “In spite of

these limitations, this study uses a very different design than prior

ones of segregation and health, and successfully replicated those

findings.

This suggests that the segregation/ health relationship is robust, and

that a questionnaire-based measure of segregation can adequately assess

this contextual variable.”

We can think of no better reason for African-Americans and other

minorities to participate in upcoming discussions and in the health and

wellness events tailored to our seniors and our soon-to-be-seniors.

There are just some things about coming “of age” in Asheville that

can’t be discovered without you!