Big, Brash and Beautiful

by Errington C. Thompson, MD –

Let me see if I can explain the phenomenon of Muhammad Ali.

I know that many, even most, have described him as “The Greatest,” and he was—but I think that it is important to understand why he was the greatest.

Muhammad Ali was more than a fighter, more than a poet. He was more than a civil rights leader. Ali was a force of nature.

So let’s strap ourselves into our DeLorean and go back in time. We need to imagine a time before “reality TV,” iPads, and cellphones.

It is the mid-1960s. There was a sameness across America. TV was just becoming the dominant medium: every household had one big grainy TV. The image was black and white and the screen was kind of oval, and men like Walter Cronkite, Morley Safer, Mike Wallace, and Chet Huntley and David Brinkley were becoming household names. They were trained journalists, not pretty-faced newsreaders, and they were known for quality reporting.

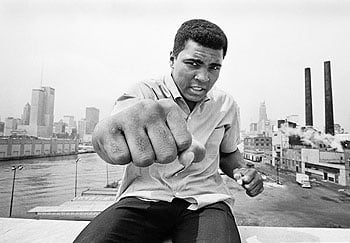

If you were an 18-year-old black kid from Louisville who had just won the light heavyweight gold medal for the U.S. in the 1960 Olympics, you were supposed to get a factory job or quietly begin your boxing career. Ali, then known as Cassius Clay, did neither. Yes, Ali decided to become a professional boxer. No, he wasn’t going to be quiet about it.

Ali was loud. He was articulate. He demanded—and got—attention and respect. No sports figure before Ali understood how to control an interview the way Ali did. Before Ali, from the 1930s to the 1960s, athletes just stood there and answered questions. The press controlled the athlete.

Ali changed all that: he controlled the press. He had a way with the spoken word that was unexpectedly clear and concise and insightful—and poetic.

Heavyweight boxing was the ultimate in male sports in the 1960s and ’70s. Every male in America watched boxing. It was what we did. Boxing was also a sport plagued with scandal. Over and over we heard that this boxer was on the take and that one took a dive. Yet somehow Ali stayed above all of that. He was never linked with the mob or organized crime. He had dignity, and pride, and strong personal ethics.

From 1964 to 1967, every boxer who counted tried to take on Ali, and he racked up one win after another. And while his performance in the ring was undeniably impressive, it was before and after the fight that Ali really shined. Nowadays we are familiar with all of the name-calling, finger-pointing, and bragging that goes on at the pre-fight weigh in. This all started with Ali. He would taunt his opponents, increasing interest in the fight and interest in Ali—and increasing his opponents’ worry about the upcoming match. And after each fight, a victorious Ali would declare that he was the greatest—and the prettiest—boxer of all-time.

During this time, the young champion changed his name from Cassius Clay (which he said was his “slave name”) to Muhammad Ali, and converted to Islam—specifically, to the Nation of Islam, the “Black Muslims.” This is no big deal now, but in the ’60s this was unheard of. No one was sure what to make of his decision. Though his freedom to choose his own religion was attractive to some, the black community overall didn’t know what to think about Black Muslims, or what to do with leaders—and rivals—like Elijah Muhammad and Malcolm X. The white community loved Ali’s athleticism but couldn’t stand his politics or religion.

In 1967, as the Vietnam War ramped up, Ali was drafted into the U.S. Army. But Ali was not going into the military. He objected for religious reasons—the very definition of a conscientious objector—and he used all his skills, intellect, character, and faith as he fought the draft. Not only was he charged with draft evasion, but he was stripped of his title as boxing’s world heavyweight champion.

Ali stated, “I ain’t got nothing against no Viet Cong; no Viet Cong never called me nigger.” His popularity soared in some communities and plummeted in others. Some hated Ali for his “un-American” stance against the war, but at the same time the American public was beginning to hate the war. Ali fought his being drafted in the courts as well as the world of public opinion, and though he lost in one court after another, his conviction for draft-dodging was finally overturned by the Supreme Court in 1971.

Ali was soon back in the ring, after being banned by the boxing commission during his three-year legal battle. He fought to get his title back, and as he fought, his purses grew. Just 10 years earlier Ali had fought for a few thousand dollars a match; now, in the early ’70s, he was fighting for millions—at a time when few corporate executives earned that much in a year.

The thing that was amazing about Ali was that he didn’t have just one or two great fights: he had dozens of them. He fought three epic fights with Joe Frazier. He broke his jaw in the early rounds with Ken Norton but fought on, losing but demonstrating a toughness and determination that everyone could admire.

Ali knew that his fights were a big deal. After all, he was the only man in history to win the heavyweight championship three times, coming back against younger fighters to reclaim the crown.

His fight with George Foreman was probably his best. He was physically outmatched. Foreman was a specimen, a man who was knocking out championship fighters left and right. In the land of heavyweight boxing, where everyone is big and strong, Foreman stood out from the crowd. Ali, 32 years old and clearly past his prime, out-thought and out-fought Foreman and finally knocked out the younger man in the eighth round.

Muhammad Ali also stood up for civil rights. He was outspoken in a time where most athletes were quiet. More importantly, he added something to the narrative. He was the embodiment of James Brown’s song, “I’m Black and I’m Proud.”

Muhammad Ali was a reality TV star before there were reality TV stars. Don’t imagine I’m diminishing Ali by comparing him to the superficial, empty-headed, reality-TV stars of today. He was the original; in an era when TV shows didn’t include blacks, anchormen and reporters were all white, and few African Americans were asked their opinions about anything, especially politics, religion, and public policy, Ali was on TV saying things that were real. He rhymed, he boasted, he taunted; even in speaking truth to power, he “danced like a butterfly and stung like a bee”—as he told about the America that existed, not the imagined one.

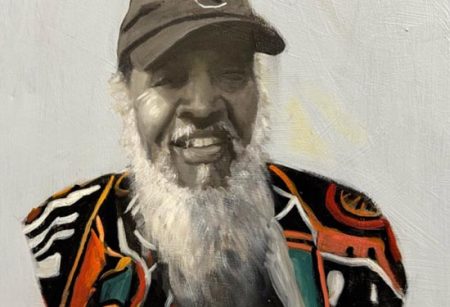

The tragedy for us is that over the last 20 years, we were robbed of hearing from Muhammad Ali because of his Parkinson’s Syndrome, which made it hard for him to speak. He was entertaining and had substance. In a nutshell, he was The Greatest.