A Dream Unraveled: A Reality-Check Retrospective

Photo: Rowland Scherman

by Deborah Louis, Micaville, NC

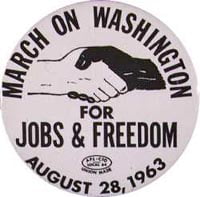

August 28 will mark the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. That’s almost three generations ago. Looking out over the Mall that day, what hopes we had! The faith in democratic process, moral authority, and ultimate political victory was electric.

Over a quarter of a million people gathered in one place at one time to appeal to the pinnacle of power to make racial justice an actuality in “the land of the free.” It was awesome, unprecedented, and compelling. And, contrary to the expectations of the District Police, FBI, and mass media, it was a crowd that looked and behaved like a very large Sunday church picnic.

The contingent from Cincinnati occupied several railroad cars. The singing was deafening for the entire ride. Roy Reuther (Walter’s brother, for whom I worked as Director of the AFL/CIO Voter Registration Drive in Hamilton County) walked up and down the aisle meeting and greeting, pep-talking, making sure everyone knew what to do when the train pulled into DC’s Union Station. Several of our number were already there in management and speaker capacities.

Cincinnati, known as “the northernmost southern city in the U.S.,” had served as a hub of movement activity from the beginning, as indeed it had for the Underground Railroad and Abolition Movement of earlier eras, and could boast having birthed a disproportionate number of its young leaders. The Queen City stood as a narrow but effective channel through which ideas and personnel moved between east and west, north and south.

Pulling off the March was monumental. Originally conceived by A. Philip Randolph and predicated on his similar initiative in 1941, the very prospect of which prompted FDR to issue Executive Order 8802 ending racial discrimination in the defense industry and establishing the FEPC (Fair Employment Practices Commission), it was seen by him as a means to move the energy flowing into the civil rights cause from mass protests to achieve access to public accommodations, to a more strategic focus on legislative action to equalize the economic playing field.

Put simply by movement organizers at the time, “Desegregating a lunch counter doesn’t mean much if you don’t have

a dime for the damn cup of coffee!” Hence the title, “…For Jobs and Freedom.” Bayard Rustin, who had organized two previous Marches on Washington and in no small measure helped to construct Randolph’s economic analysis, took the reins.

In a matter of weeks he had recruited a national organizing committee of courageous, energetic, and tireless young black and white veterans of the movement’s front lines of both the inner cities of the North and rural outposts of the South, and let them loose on the rapidly expanding and solidifying movement action and communications network.

As one might imagine, it is not easy to organize organizers. We are an assertive and sensibly suspicious lot. The March was, however, an idea whose time had come. With Rustin’s organizational genius and the preceding three years of relentless movement activity on both sides of the Mason-Dixon line the March was not a hard sell within movement circles or out in the support community.

The prospect of a national stage from which to express what we had learned from our experience to date and what was still needed to make this a genuinely inclusive America appealed to even the most cynical among us. The full spectrum of viewpoints was to be represented in a star-studded, day-long program of information, inspiration, and meaningful policy advocacy.

That is, up until the actual March. The forced revision of John Lewis’ speech in exchange for being allowed to speak at all, right before he was scheduled to take the podium, ended this optimism once and for all for the more cognizant, front-line movement leadership.

It was their experience and viewpoint, warning of the probability of violent eruption in the nation’s black communities if economic barriers continued to be ignored and social mobility restricted, that were handily excised from the Lewis narrative.

Dr. King’s hypnotic “I have a dream”—a snippet of another preacher’s sermon he had used previously to satisfying effect–became the defining sentiment of the event. Tens of thousands of participants who were relatively removed from the actual struggle returned home to do and think the same things they had been doing and thinking prior to the March, but in that gratifying afterglow of being patted on the head by an icon.

It was not long before what we saw coming came, in Cincinnati and elsewhere, in the form of (police-instigated) riots at the bottom and assassinations at the top. We had not, however, foreseen the initiation of new genocidal techniques in the form of crack, “welfare reform,” and a burgeoning private prison industry, or the gradual erosion of our democratic institutions overall.

While the years immediately following the March marked enormous and documentable gains in the more equitable diffusion of political, economic, and social power across America’s disenfranchised communities, as with Reconstruction the forces of reaction soon regained their footing and embarked upon a covert and systematic backlash de tutti backlashes that might well be likened to a quiet and surreptitious coup d’etat.

Despite the overwhelming effectiveness of the Civil Rights Act and Poverty Program in empowering and raising the standard of living for millions of Americans hitherto excluded by virtue of color or gender, all of the policies that made that work were gradually rescinded, and renewed strategies to dismantle the gains of previous eras (labor, consumer, and environmental protections, public education, Social Security, and even due process itself) ushered in. We are not only back to where we were in 1960, in many ways we are back to where we were in 1930!

So, as we enter the season of assault by nostalgic reminisces of the soothing and wishful words of Dr. King and a memorable event in our not-that-distant past, let us resist the inclination to romanticize that history and pat ourselves on the back, and reflect, perhaps, upon the Trayvon Martin verdict and passage of the Texas “abortion” law in just the past few weeks, and rather remind ourselves of what was achieved, what was lost, and what we need to do to take back our country.

©2013 by Deborah Louis

Dr. Louis is not only a veteran of the civil rights movement of the early 1960s, she also wrote the only comprehensive history of that period in the continuing struggle for racial justice in the U.S.: And We Are Not Saved: A History of the Movement as People (Doubleday 1970; Press at Water’s Edge 1997).

Readers may listen to a recent interview with her about the book on WPFW, Washington DC’s Pacifica/NPR station, www.voxunion.com.