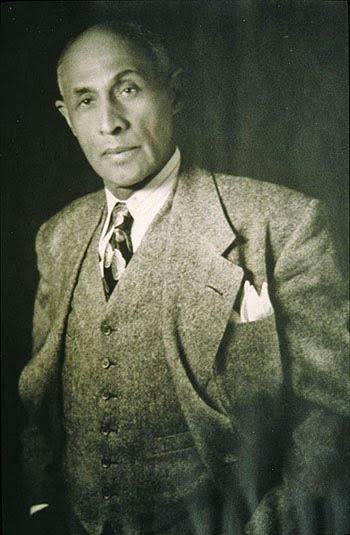

Madison Hemings

By law, Thomas Jefferson and Sally Heming’s children were considered Black, even though they could pass for White.

Some White people are actually Black.

After Thomas Jefferson’s death, four of his six children had a decision to make. Two had already run away and eventually moved into White society. They were all the products of the rape of an enslaved woman, Sally Hemings, who was the product of the rape of a “full-blooded African” woman. Therefore, by law, they were considered Black, even though they could pass for White. The remaining three intermarried with White spouses and chose to become White.

But Madison Hemings stayed Black.

He married a Black woman, moved into an all-Black community and became an abolitionist. Why he chose to do so is interesting. He knew White people were liars. According to him, when he was born, another guy begged Sally Hemings to name her son “Madison” in exchange for a “very fine present.” Sally did it, but, according to Madison, she never received the gift, “like many promises of White folk.”

For most of human history, the term “race” didn’t exist. It emerged in the late 16th century to describe a type of thing, including a “race of wine,” or a “race of saints.” Before then, every culture on the planet had their own stratification. Europeans considered Asians to be “White.” Even when Enlightenment-era philosophers began categorizing species, they subdivided humans by geographic regions.

White People Invented Whiteness

During colonization, Catholic priests were initially against enslavement, and when colonizers objected, others pointed out slavery in other empires, with priests arguing that Greeks, Romans, etc. were different races. That’s when—according to professor Gregory Jay— “Whiteness emerged as what we now call a ‘pan-ethnic’ category, a way of merging a variety of European ethnic populations into a single ‘race.’”

But even then, Whiteness wasn’t clearly defined. In 1705, Virginia banned criminals, and “any negro, mulatto, or Indian” from holding office. Racial integrity laws were passed by the General Assembly to protect “Whiteness” against what many Virginians perceived to be the negative effects of race-mixing. They included the Racial Integrity Act of 1924; the Public Assemblages Act of 1926, which required all public meeting spaces to be strictly segregated; and a third act, passed in 1930, that defined as Black a person who has even a trace of African American ancestry.

This way of defining Whiteness as a kind of purity in bloodline became known as the “one drop rule.” These laws arrived at a time when a pseudo-science of White superiority known as eugenics gained support by groups like the Anglo-Saxon Clubs of America, which argued that the mixing of Whites, African Americans, and Virginia Indians could cause great societal harm, despite the fact that the races had been intermixed since European settlement. From his position as Virginia’s state registrar of vital statistics, Walter A. Plecker micromanaged the racial classifications of Virginians, often worrying that Blacks were attempting to pass as White.

Virginia Indians were particularly incensed by the laws, and by Plecker in particular, because the state seemed intent on removing any legal recognition of Indian identity in favor of the broader category “colored.” After one failed try, lawmakers largely achieved this goal in 1930, drawing negative reaction from the black press. The Racial Integrity Act remained on the books until 1967, when the US Supreme Court, in Loving v. Virginia, found its prohibition of interracial marriage to be unconstitutional. In 2001, the General Assembly denounced the act, and eugenics, as racist.

White people are people who say they are White

At one time, the Irish weren’t considered white. Or Jews. Or Italians. They were only accepted into the club when they proved they could join in the oppression of people who were not like them. At one time, Hispanic people were not white. Now there are White Hispanics and “non-White Hispanics.”

In his book The Souls of White Folk, W.E.B. Du Bois said, “The discovery of personal Whiteness among peoples is a very modern thing—a nineteenth and twentieth century matter, indeed. The ancient world would have laughed at such a distinction. The Middle Age regarded skin color with mild curiosity; and even up into the eighteenth century we were hammering our national manikins into one, great, Universal Man, with fine frenzy which ignored color and race even more than birth. Today we have changed all that, and the world in a sudden, emotional conversion has discovered that it is White and by that token, wonderful!”