Honoring Our Veterans

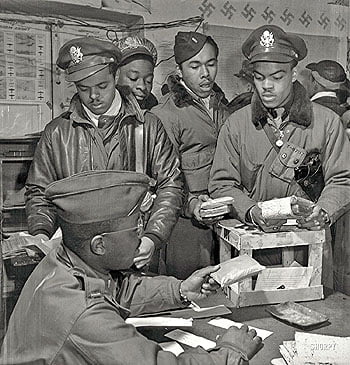

Heroes Like None Other: The legacy of the Tuskegee Airmen.

By Joe Elliott

They were heroes like none other. Beginning in 1941, shortly before America’s entry into World War II, a group of young black men started training as military pilots at a segregated air base in Tuskegee, Alabama. The most famous of these was the 332nd Fighter Group (later 99th Fighter Squadron), familiar today to many as the Red Tails Squadron for the distinctive red markings on the tails of their planes, but better known as the Tuskegee Airmen.

For the Airmen, the toughest part of their job wasn’t so much about learning to fly those big planes as it was battling the prevailing race prejudice of their day. And while they would face a formidable foe in the skies over Germany and Italy, they were destined to face an even greater one at home.

The fact was that most white Americans simply didn’t believe they were up to the task. Among the most widespread and popular images of blacks of the era was that of Stepin Fetchit, played by actor Lincoln Perry, humorously known as “the Laziest Man in the World.” The huge popularity of this character among white audiences spawned a host of screen imitators (Sleep ‘n Eat, Man Tan Moreland), all of whom were played strictly for laughs, all of whom were portrayed as mostly lazy, shiftless and illiterate.

A well-known 1925 Army War College study of black troops in World War I had concluded they were as a group “mentally inferior and barely fit for combat.”

It was upon this forbidding stage that the Tuskegee “experiment” began in 1941. As might be expected, the reaction of the white community to the news that a bunch of “colored boys” were being trained to fly expensive military aircraft was largely negative. But fly they did. After their initial training in the States, units of the Airmen received additional training in Europe before undertaking their first missions in June of 1943.

These freshmen missions involved strafing Axis positions across North Africa. Later more Airmen were activated and joined the 99th Fighter Squadron. Their primary objective was to see that Allied bombers made it safely to and from their bombing sites. These Airmen were reportedly among the Army Air Force’s most successful fighter groups, losing only 25 bombers during the time they served as escorts.

According to the Wilson V. Eagleson Chapter website, “A total of 992 pilots graduated from the Tuskegee program between 1941 and 1946. Of these, about 450 Tuskegee Airmen flew combat missions over North Africa and Europe in a variety of aircraft including the P-40, P-39, P-47, and P-51 and tallied an impressive record.

That record included 1,578 combat missions and 15,533 sorties in which they destroyed 261 enemy aircraft. Their record also includes the first unit to shoot down a German jet fighter and the first unit to sink an all-metal destroyer with machine gun fire.

For these and other acts, graduates of the Tuskegee program were awarded an array of over 850 medals for heroic or meritorious achievements.”

The mission of the Airmen was to help win the war, not advance the cause of civil rights. However, in doing their job, (and doing it exceptionally well), they proved once and for all that people of color were capable of far more than most white Americans realized, or cared to acknowledge for that matter. Their courageous, skillful work in many ways helped set the stage for the coming revolution.

Had there been no Tuskegee Airmen there might still have been a Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King, Jr., but the work of these later heroes would have been harder without the contributions of the Red Tail pilots and crews in the 1940s. In this sense the Airmen are heroes on two fronts, having helped advanced the cause of liberty and freedom throughout the world but perhaps nowhere more so than right here at home.