New Hopes for Reconciliation from New Segregations

“It’s so hard because of what’s going on in our society, and we don’t even know how to talk about race…” – Lutrell-Rowland

“It’s so hard because of what’s going on in our society, and we don’t even know how to talk about race…” – Lutrell-Rowland

By Tamika M. Murray

Does the documentary film New Segregations build bridges to cultural understanding or propagate a culture of continued misunderstanding?

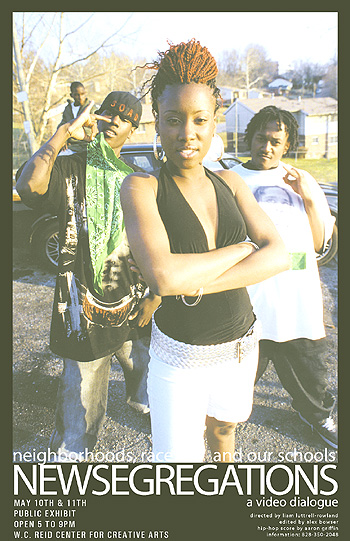

Aaron Griffin and Liam Lutrell-Rowland’s motivation for the documentary sheds light on the perspective of young people who continue to struggle, not only in the school system but in the isolated communities in which they live. New Segregations raises questions of a city divided by racialism and holds a light to a greater social failure that has manifested itself through the lives of the children in our community.

“The

film is about how to give these kids a voice in a segregated society

and the difficulties of that,” said Lutrell-Rowland. “And it’s about

the kind of people that interact with them in a way that is effective.”

|

| Aaron Griffin |

In cooperation

with the W.C. Reid Center of Creative Arts, the Randolph Learning

Center, Voices of Parents and the Lee Walker Heights Community Center,

New Segregations featured candid interviews with students, parents and

a diverse group of adults who work both inside and outside the school

system to challenge and inspire them, while fighting for their rights

to equal education.

The 45-minute

documentary offers the viewer more than the opportunity to hear what

young people have to say in our community; it provides a historical

context and the chance to see the tangible effects of gentrification,

the parking lots that were once homes or Black-owned businesses, the

Black schools transformed into community centers and reveals a

generation of young voices that need to be heard.

“The movie is

about race in a lot of ways. These two parts of Asheville are very

segregated, and both me and Aaron are coming from a strong place of

believing that,” said Lutrell-Rowland.

According to the

North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, some 1,129 suspensions

of Black students occurred within the 2006-2007 academic school year.

While this figure may include repeated suspensions by some of the same

students, only 195 suspensions occurred within the White student

population. In a school system with predominantly White teachers and

administrators, a problem persists with a great number of

student-teacher interactions.

But there is a

danger that comes with creating a film with the intent of addressing

issues of race and education. Lutrell-Rowland struggled with the idea

of “coming into the Black community and making a film that will be seen

in the White community,” said Lutrell-Rowland. “There was a fine line I

had to walk personally, especially when you’re dealing with the

imbalances of privilege. I don’t want to take these kids stories out of

their community and not have it be for them. But I also know that some

of this stuff needs to be heard. So, how can we convey it in a way that

feels safe, but can also challenges people.”

|

| Liam Lutrell-Rowland |

“The film is

true. It’s real. Real people. Real stories. Real lives,” said Griffin.

In order for a teacher to “really understand a child,” he believes they

“need to really understand where [the students] come from. Like those

people in the Black community who grew up here. It’s no big thing. It’s

every day life.”

Both Griffin and

Lutrell-Rowland believe the film can be used as a cultural teaching

tool to educate established teachers and rising teachers in the area.

They hope the film will inspire educators, administrators and policy

makers to look beyond the surface of the defiant child who may appear

unwilling to participate in his or her education.

But not everyone

found the film to be educational or empowering for people working

within the school system. In a letter to the Mountain Xpress, RLC

teacher Cedric Nash, an Asheville native and former resident of Lee

Walker Heights said this: “It disheartens me to hear students I have

taught say that teachers don’t care and do not listen.”

Nash felt the

film was problematic because students vented their frustrations in the

classroom, but did not show a child laying his head on the desk,

refusing to do the work. “I tell them every day that I love them,’ said

Nash who moved back to Asheville to give back to the community through

his work with young people.

Asheville City

School spokesperson, Charlie Glazener, who has not yet seen the film,

said the school system as a whole did not get involved with the project

because they felt the project would be “one-sided” and that it would be

based on an “agenda.” Glazener said also that the school system for the

most part was “racially balanced” and the members of the school board

have spoken of plans to reintegrate the predominantly Black Randolph

Learning Center and Asheville Preparatory Academy back into the school

system.

But frustrated

parents and students need more than racial balance. The documentary

climaxes when a 17-year-old boy, a high school drop-out, dies of a

gunshot wound. Many of the youth in the film were deeply affected and

forced to think of their own lives as well as their futures.

“We’ve tried a

number of times to devise a plan to help educate these kids that

[school system administrators] are saying don’t want to learn,” said

Larry James, co-founder of Voices for Parents, a group that would like

to participate in the mediation process with families and

administrators. “They ask for us to get involved, but when the African

Americans try to get involved, they don’t pay attention,” he said.

James believes a “better understanding” between White teachers and

Black students will lead to a higher success rate for the Black student

population.

In response to a

statement made by Superintendent Robert Logan, at the State of Black

Asheville Conference, African American students are more “dramatic” and

require tougher disciplinary policies than their White counterparts.

However, Voices of Parents co-founder Larry James said, “We have to

have versatile teachers to understand children who are in a diverse

situation. Maybe [Voices of Parents] can find out something

[administrators] can’t.”

Elinor

Brown-Earle, program director of Youthful H.A.N.D., has found through

her experience with the after school program at Lee Walker Heights,

that children often act out when they are struggling academically. She

believes the city school system could effectively address students who

have difficulty with reading through the Read First Program. [The

curriculum] “teaches children explicit phonics and phonetic awareness.

These programs

have been approved by the United States Education department, the

National Literacy Council and the National Institute of Child Health

and Development,” said Brown-Earle. She believes the responsibility of

teaching children to read and write lies with the school and that

community-centered programs work to assist children with the other

aspects of their education.

“It’s so hard

because of what’s going on in our society, and we don’t even know how

to talk about race,” said Lutrell-Rowland. “I think there are a lot of

issues in terms of giving these kids an equal education. But I do think

there is hope. I think there’s ways for the schools to work with the

community. We have the resources.”

The film is an

invitation, said Griffin “to see who we are. To see how we live — so

you can understand us. We’re talking about dialogue creating change. If

someone has a different view and they feel offended, and we actually

sit down and talk… then it’s a beautiful thing.

That’s what we

encourage, and that’s what makes a difference. I feel the film is

successful if any individual watches the film and has something to say.

No matter if it’s negative or positive. If it starts dialogue, it

starts change… then it’s successful.”