Burton Street Community Center

Part of “Park Views,” an Asheville Parks & Recreation series.

“Plant early, dig in now! Plant and hoe, make that garden grow. Plant it, work it, day and night; So when the winter snow is falling, you will be sure to eat right.”

Civic leader and renaissance man Edward W. Pearson Sr. used this slogan when organizing the Buncombe County District Agricultural Fair, but it can also be applied to the neighborhood that blossomed from seeds he planted and the community center that occupies the building of the former Burton Street School.

E.W. Pearson

Born in Glen Alpine in 1872, Pearson moved to Asheville in 1906 after serving as a member of the Buffalo Soldiers, the segregated 9th Cavalry unit of the US Army that fought alongside Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders in the Spanish-American War. His arrival and real estate experience learned in Chicago was a harmonious fit for Asheville’s real estate boom of the early 20th century, leading to the city’s first subdivision for Black families on the location of today’s Burton Street (originally named Buffalo Street) neighborhood.

Originally extending to Westwood Place, Pearson’s development was called Park View and consisted largely of rural, wooded lots. Many tenant farmers from the Carolinas and neighboring states relocated to Asheville to establish their own small family farms in Park View while working in construction, tourism, domestic housework, and other industries. The population increased and streets, churches, stores, and a school were built as a vibrant neighborhood came to life.

Pearson held the first Buncombe County District Agricultural Fair in 1913 in Pearson’s Park, located on Fayetteville Street. Black residents from throughout western North Carolina traveled to Asheville to participate in the fair, which grew to include parades, amusement rides, and games. He offered cash prizes for the best exhibits in agriculture, fair variety, canned fruits and jellies, baked goods, sewing and handicraft, and flower arrangements.

Aside from organizing the annual fair, Pearson in 1916 established the Royal Giants, a baseball team that played other semi-professional Black clubs from North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia in Pearson’s Park and Oates Park in Southside. He also operated several businesses including Mountain City Mutual Insurance Co. and Piedmont Shoe Co., a mail order shoe venture. His vision to improve the quality of life for the city’s Black community members included founding the first business league for Black businessmen in Asheville and establishing the local chapter of NAACP.

He also operated E.W. Pearson Grocery Co., which included a big room for social meetings, Piccolo jukebox, pool table, and playground complete with swings, seesaws, and a merry-go-round. Throughout the year, the Pearson family hosted concerts and large gatherings for family members, friends, and neighbors at the store and their home located behind the store. Pearson played multiple instruments and would perform on Sundays with his three children.

After his father passed away in 1946, E.W. Pearson Jr. operated a music club named Blue Note Casino in the former store, located across the street from the current community center.

Burton Street School

The current community center occupies a building erected in 1928. An earlier two-room building opened as Burton Street School on the same site in 1916 as an elementary branch of Buncombe County Schools (before West Asheville was annexed by Asheville in 1917); however, the tract of land dates to 1884 when it was transferred to the public school committee with the purpose of establishing a school for Black students. Hattie H. Love was an early teacher who later became principal and served as secretary of the NAACP state conference.

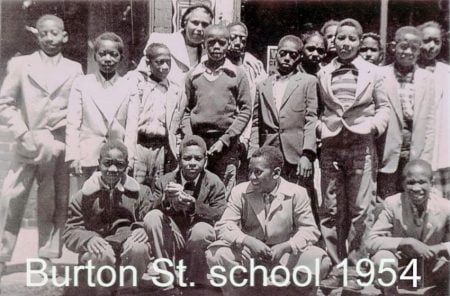

The original building accommodated about 120 pupils with the first three grades taught in the morning and fourth, fifth, and sixth grades taught in the afternoon. When the second building opened with four classrooms and an auditorium, lunch room, and library, students were able to attend all day. After Burton Street, most students went to Hill Street School for middle grades.

In 1950, Burton Street School began hosting recreation programs supervised by Isaiah Rice and Mrs. C. W. James including group singing, dramatics, games, and table games. The school closed as part of Asheville City Schools’ desegregation plan in 1965 and was deeded to the City of Asheville in 1977.

Neighbors, Not Borders, Define Community

In the late-1950s, construction of Smoky Park Bridge (now Capt. Jeffrey Bowen Bridge) allowed for the westward extension of Patton Avenue, cutting through woods and burying creeks and springs. Construction of I-240 in the 1960s bisected the community even further, creating dead end roads, eliminating houses, and completely isolating families who lived on Argyle Lane and other streets that had once been part of the neighborhood. However, Burton Street had been shaped by resiliency since it began and community connections endured.

On April 1, 1963, Pearson’s former store building became Burton Street Community Center. Pearson’s daughter Iola Byers was named as the center’s director and served that role until 1992. Known as “Miss Iola,” Byers was the first Black woman to become a deputy with the Buncombe County Sheriff’s Office and cared deeply about the community her father had established. She was never without fresh ideas for lively programs and entertainment.

As APR leveraged federal grants to expand services in the 1970s, the community center relocated to the 1928 school building which was renovated to include a kitchen, sewing room, fitness center, billiards room, meeting space, and accessible restrooms. After sitting vacant, the building was in need of a new roof, complete electrical rewiring, new doors and windows, and replacement of floors and walls in some rooms.

The building served as more than just a community center, acting as the site for neighborhood meetings, social gatherings, and safe space before the APR Afterschool program was established. “We have a lot of working mothers in this area,” Byers said in a 1983 Asheville Citizen-Times article. “Some of their children do their homework here. If necessary, if parents are late coming home, we stay here until they get home. We adjust to fit the need. One advantage of living and working in the same community is that you get to know problems or needs that otherwise you wouldn’t know about. We are a center of information; if I don’t know what to do, I can always contact somebody.”

Burton Street Revival

Through the 1980s and 1990s, founding families of the neighborhood left the area or passed away, leaving homes to be abandoned, sold, or rented to newcomers. The community center adapted with the times, adding nutrition programs and computers, but the shrinking, once-tight community network contributed to growing influx of drug and other crime activity.

With the exception of programs at Burton Street Community Center (particularly those for kids, teens, and older adults), residents felt they were not receiving essential support and services from city government. A 1996 City Council decision to permit storage units in the residential section of the neighborhood sparked a new era of community activism—with organizing meeting usually taking place at the center. Neighbors, already working with Asheville Police Department to rid their streets of crime, began working on a master plan to guide the future of their community.

When APR unveiled its first long-range comprehensive parks and recreation master plan in 1998, major investments to improve the community center building were included. A public bond referendum to fund these investments failed by 357 votes in 1999, but public discussion was encouraging enough that City Council approved a property tax increase and set aside a portion of the increase to clean up community centers, build sports fields, and spruce up green spaces.

The economic downturn of 2001 caused challenges, but Burton Street residents fought to keep their community center open and celebrated the installation of a new playground. As part of the larger neighborhood-oriented Weed and Seed program, building improvements and upgrades were added to accommodate additional services.

Today, Tomorrow, and Beyond

E.W. Pearson stands watch over the Burton Street neighborhood in the form of a mural on the community center that was unveiled at the resurrected Burton Street Agricultural Fair in 2012, a reminder that history is never far from the minds of those who live nearby. Since the 1990s, a state highway project has threatened to again cut into the neighborhood and destroy homes. In 2018, City Council unanimously approved a plan presented by Burton Street Neighborhood Association to improve the community center, upgrade sidewalks and pedestrian connections, and take other measures to work with residents to continue the neighborhood’s revitalization.

Solar panels were recently added to the community center and the park that surrounds the building is set to receive a substantial makeover to meet the neighborhood’s modern needs.

As Burton Street Community Center prepares for the future, another quote from Iola Byers about her father seems fitting: “I can just see him, standing back, his arms folded, being so proud of all this progress. Little kids can’t go far from home and if you can provide this within a community, that is good. He’d be so proud to see all this.”

This article is part of Park Views, a weekly Asheville Parks & Recreation series that explores the history of the city’s public parks and community centers—and the mountain spirit that helped make them the unique spaces they are today. Read more from the series at www.ashevillenc.gov/news/category/park-views.