Housing, Revisited: A discussion with former Asheville Housing Authority Director David Jones

|

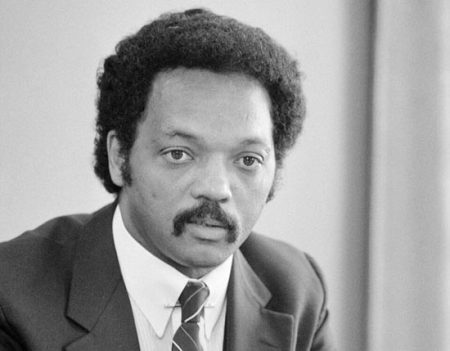

| David Jones, former director of the Asheville Housing Authority. Photo: Urban News. |

by Sarah Williams

In recent months public attention has been drawn to the long history of Urban Renewal. Begun in 1935 and jump-started shortly after World War II, urban renewal has been – and still is – praised or demonized depending on where one stands.

Some perceived it as a radical overreaching by federal, state, and local governments; others envisioned an opportunity to help lift people out of poverty; while cynics and profiteers saw a way to get rid of the slums and profit by taking advantage of the displaced residents’ lack of knowledge, resources, and political power. Writer James Baldwin called it “Negro removal,” and activist Jane Jacobs critiqued it harshly in her groundbreaking 1961 book, “The Death and Life of Great American Cities.”

Now, three generations after the first Depression-era programs began,

when much of the replacement housing built under various city

“revitalization” programs is itself in need of replacement, urban

renewal’s origins and its impact on communities are being revisited in

public forums. Scholars, community groups, cultural institutions, and

government entities are studying, analyzing, discussing, and arguing,

not about whether urban renewal made a difference, but whether the

difference it made in the lives of individuals and communities was

good, bad, or somewhere in between.

Blight, poverty, and upward mobility

David Jones was Executive Director of the Asheville Housing Authority

from 1976 until his retirement in 2005. From his perspective, the

purpose and value of public housing programs is “removing all

substandard housing conditions to make a more livable environment for

people who cannot do for themselves.” That work included eliminating

“the blighting influence of substandard housing and providing upward

mobility for people living in these areas.”

This winter a large group of Asheville residents attended a meeting at

the YMI to discuss urban renewal, and a frequent comment was that under

the last big urban renewal push in the 1960s and ’70s, a great deal was

taken from the black communities, even the sense of community they knew

and appreciated. Some feel that little was given back.

Still a strong advocate of housing programs, Jones attended the

meeting. At first, he says, he “thought about disagreeing with the

people,” but then he thought about a professor who had made an

impression on him when he asked them to look at a wall in the room and

tell him what they saw.

“Different people saw different things. The professor explained that

they were all right because they were speaking from their own

perspectives and experiences. This was the case with the people who

felt that so many things that meant something to them had been

destroyed. They were all right, based on their own experiences and

perspectives.”

Viewpoints differ, especially on the question of fairness. Various

housing laws from the Roosevelt administration onwards have provided

for different ways of valuing property as well as compensating owners

for it. Government bodies have been empowered to set a

take-it-or-leave-it price, to negotiate with owners, or to use eminent

domain to acquire residents’ homes and businesses. They have also been

authorized to sell the acquired property to the highest bidder for

redevelopment, or to sell it at a bargain basement price – or even give

it away – through private agreements with developers. Rarely have those

who were “removed” reaped the benefits.

|

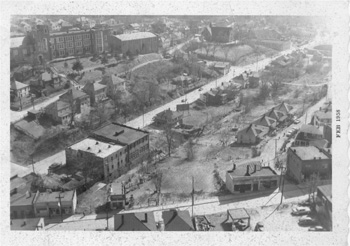

| This photo from 1958 shows South Charlotte Street, then known as Valley Street. Stephens-Lee is pictured in the upper left hand corner. |

In meeting with the organizers of the YMI meeting, Jones says, he told

them that what they were saying should be documented, “but it needed to

be documented right.” His own records were turned over to the City of

Asheville: “Everything was a matter of public record, and the records

are available. People were living in neglected neighborhoods at that

time and pictures were taken of the way people were living. The records

pull together a lot of the history of black people in Asheville.”

Reflecting on the long history of urban development and renewal, Jones

believes that not only such programs, but public entities like the

Asheville Housing Authority, as well as individuals who ran them,

should be viewed in a positive light.

Jones was involved in Asheville’s first big urban renewal project. When

the city learned that money was available for city improvements, it

applied for funds for a downtown development project that would stretch

from Beaucatcher Tunnel west almost to Lexington Avenue, in a swath

that included the public health building, the law building, and parking

for First Baptist Church, the old laundromat on Pack Square and the

land where the BB&T building stands. Jones, who was involved in

acquiring properties for removal, says, “There were no black businesses

in sight in the civic redevelopment area. The buildings were acquired

through acquisitions and condemnation.”

Catching hell, earning respect

When the city’s attention turned to the next big project, it took in

“East Riverside from Hilliard Avenue, Ashland Avenue, all the way up

McDowell, to Walton Street, down to the train station down on the

river, up to Lyman Avenue,” says Jones. “It was the largest single

urban renewal project in the southeast.

“People say the next thing they knew was that they looked up and they

saw the bulldozers, but that’s not true. All of these urban renewal

projects were pretty complicated. The city had to apply for and receive

funds for these areas. The city then had to clearly define what those

areas would be, and a referendum had to be held for the people of the

city of Asheville to vote on it,” says Jones. He points out that the

first referendum failed.

“The criteria had to be a depressed area with some of the worst slum

conditions. People have talked about all of the black businesses that

left from there. There were some black businesses, but many of the

buildings were not black owned. Some of the businesses were gaming

establishments and these were closed. The second referendum was voted

on and it passed, and urban renewal came about in the area.”

As supervisor of the project, Jones and his staff renovated over 200

houses with grants and loans, and he acknowledges that the process was

touchy. Urban renewal meant taking people’s houses, tearing up

neighborhoods and rebuilding; it meant relocating people and disrupting

extended families and long-established neighborhood ties. It also meant

catching hell from every side because of demands from federal

government, state government, local government, and residents who

wouldn’t like what had to be done.”

Jones says that he conducted business honorably, and that as a result

he earned great respect from the community. Yet there is still

controversy surrounding the fairness of the process in Asheville.

Imminent bulldozers, eminent domain

Were black businesses in the East End, like the Hart Wilkins building,

taken by eminent domain or by negotiation? “There were businesses,” he

says, “but no major businesses in these depressed areas. Very few

people took the route of refusing to sell.” For those who did refuse,

“their property could have been taken by eminent domain,” but the

Housing Authority was required to pay the established price or whatever

cost the court awarded, and in addition,” Jones asserts, “they would

pay the court costs for those people going to court.”

He explains the process: “After the city declared locales as depressed

area and clearly defined where these areas were, they were required by

law to have a neighborhood committee work along with the architects to

develop the plan. That map had to declare up front where all of the

residential units would be, where the commercial would be, and where

the public properties would be. These were all voted on. Then you had a

committee that worked to pull it all together. This was how they got

the property for expansion for the South French Broad school, the YWCA,

the fire station, and Livingston Street park.

“The maps that had been developed had to be displayed, by law, so that

all could come and look at property to see what the disposition of it

was and what would be in its place. You had to have all of these things

in place for it to be an urban renewal project. It also required

Housing Authority, planning and zoning, City Council, and HUD approval

before any money could be spent.

According to Jones, all of these maps should still be in existence,

acquisition maps showing what was to be acquired and disposition maps

showing what type of commercial or residential structure would be built

on each acquired property.

He is unapologetic about the work of the Housing Authority. “The

Housing Authority had to do something where Erskine and Walton Streets

are. Livingston Street and that area were depressed. A clause in the

law said they had to do one-for-one replacement, so in order to tear

out every house that had to be torn out, they had to make way for

Erskine and Walton Street developments. The people whose houses had

been torn down had first opportunity, so 122 people moved into

Erskine-Walton Street development once it was built.”

The price for being uprooted

One controversy that has long simmered is how and why homeowners –

people who might have been very poor, and whose houses were substandard

but still belonged to THEM – were unable to return to the community.

According to Jones, “Many of the people from the community purchased

dollar-a-lot, constructed homes, and moved back into the community, and

are still living in the homes.

Some reports state: They were forced to sell the property they owned,

but many were then redlined when they applied for loans to buy

replacement homes. Thus they were forced into public rental housing –

having lost what little equity they had had – or else had to move to

other neighborhoods altogether, often away from friends, family, and

community ties.

The “dollar-a-lot program,” was designed to allow former residents to

buy property in the neighborhoods they chose. According to Jones,

“those people had the first shot at those, although there was a process

they had to go through. They had to have approval because the state law

said the Housing Authority had to get each property appraised. Once the

price was established and given to the city, for example, if the price

was $15,000, by state law, the Housing Authority had to get $15,000.

The city set up a till for that.

“That”, says Jones, “was Larry Holt’s idea. Holt was deputy director of

the Housing Authority, and he suggested that if the city put up all but

one dollar (the dollar paid by the buyer), the city would get their

money back through taxes, increased property values, etc.” Jones liked

the idea and convinced the city to establish a pot of money for that

purpose.

“Larry Holt’s vision of the dollar a lot program took off all over the

nation; it was one of the greatest things for the cities. The people

were able to get that land. They might not have gotten the lot they

wanted but they got one near the one they wanted.

“As an example,” he adds, “The people in East Riverside had the option

to sell. They got a good deal: they were paid the fair market value of

the house and they were given $15,000, which in a lot of instances,

between the purchase price of their house and the $15,000 they got,

that was enough to purchase a house. Some of them had to have some

loans, and some of them still have the loans.”

But he acknowledges that not everyone was able to buy a house. Some

simply didn’t have the resources to buy, others lacked the stability or

character. “You’ll always have poor people, and so we were able to

provide some funds and housing for these people. Some neighbors

complained about what the people were doing once they moved into a

place.” His own charge in life, he says, was “to eliminate the slums

they were living in and move them into a good standard decent house. It

was up to someone else to help change what they were doing. I couldn’t

tell them about how they were living their lives.”

The next chapter

The last project Jones worked on was Project 19, a transitional housing

program. Under Project 19 people move in, pay their rent, go through

home ownership training and other training programs while they get

established and on their feet. That would include signing a contract

that they would learn to live up to certain standards. After a certain

amount of time, they have to move on, either back into the private

sector or to home ownership. Then another family could move in.

As for the HOPE VI Program, Jones is optimistic based on what friends

in other communities have told him. But, he points out, “I brought in,

in one year, $30,000,000 to the city to change barrack style housing

into townhouses. I’d be very foolish to put millions of dollars in a

development, then tear it down to build something else. You utilize

what you have.”