Equity Erased: Forced Sales Hurt Heirs, Poor Homeowners

Asheville area homeowners, many elderly and/or Black, have been left embittered and poorer by their encounters with local real estate investor Robert Perry Tucker II and his associates.

By Sally Kestin, Part II of a series by Asheville Watchdog –

Asheville area homeowners, many elderly and/or Black, have been left embittered and poorer by their encounters with local real estate investor Robert Perry Tucker II and his associates.

Signed deed from fingerless man

Relatives of George G. Wilson Jr. question how he could have signed a deed to Tucker’s company for his share of the family property in 2018 since the fingers on both of his hands had been amputated more than a year earlier, in February 2017. Wilson had only his thumbs remaining, said his sister, Shirley Brown.

Wilson was 67, in debt and living without heat or electricity in a Shiloh home that he’d inherited with his two siblings. In October 2018 the city of Asheville sent a letter warning of fines if Wilson continued living in the house that had already been deemed unsafe for occupancy.

Wilson called his friend, Maugherite Poole, and said, “ ‘I need some help,’ ” Poole told Asheville Watchdog. She said she introduced him to someone she knew through her fiance’s church, Lisa Roberts, who had been interested in properties in the area.

Poole said she went with Roberts to Wilson’s home and later accompanied him to an attorney’s office, where he sold his one-third interest in the property to a Tucker company. Poole said she wasn’t present for the discussions and did not know how much Wilson received.

Wilson died in June. His siblings said Wilson was addicted to crack cocaine, and they didn’t know about the sale until later. “He needed the cash because he was doing drugs,” said his brother, Kenneth Wilson.

The deed indicates a sale price of $8,000. Brown said George Wilson told her he received $1,000, and some additional money may have been paid on a debt he owed from a car accident. Court records show Geico won a $10,861 judgment against Wilson that was settled two weeks after the deed was recorded.

At the time, the property had a total tax value of $71,900. The land alone was valued at $35,800, making George Wilson’s one-third interest worth about $12,000 to $24,000.

The signature on the deed, with Wilson’s first, middle and last names in cursive handwriting, appears similar to his pre-amputation signature on other documents. But after the surgery, his sister said, he signed with just his initials, like this health record from May.

Melvin Foster, a cousin who said he visited George Wilson weekly, told Asheville Watchdog he saw Wilson try to sign his name after he lost his fingers. “I’d seen him try to write before. He couldn’t do it,” Foster said.

Henry notarized the deed, affirming that George Wilson Jr. signed it in his presence. “I don’t specifically recall” it, he told Asheville Watchdog. “But I don’t notarize things without people being in front of me.” He declined further comment, and Tucker did not respond to an email with questions about the transaction.

Kenneth Wilson said a man who identified himself as a lawyer had come to his house, said he had bought George Wilson’s interest and offered him $12,000. Wilson said he refused. Now he and his sister co-own the property with Tucker’s company. They had hoped to renovate the house and keep it in the family, Kenneth Wilson said.

“My sister’s son was going to take over, try to make a rental property of it,” Kenneth Wilson said. “Seems like we can’t do nothing now.”

A deed from prison

Tucker retained a private investigator to locate Robert Buckner, Jr., the son and sole heir of an Asheville man who died in 2020, and found him in a Florida prison, Tucker said in a sworn statement. Tucker’s company obtained a deed from Buckner for his father’s house for $10,000.

A week later, the estate administrator sold the house for $148,000. Tucker then claimed that the net proceeds, $136,000, should go to his company, not the son.

In a virtual court hearing in April, Buckner testified that Tucker had promised him a second, undetermined payment dependent on the sale price of the house, and that he hadn’t understood the documents he signed. “There’s no way I would sell my father’s home and property for $10,000,” he said.

Henry asked, “Where did you get the understanding that you would receive the secondary payment?”

“In conversations, sir, with Mr. Tucker,” Buckner replied.

Henry asked Tucker if he or his company had agreed to any other payment besides $10,000. “Absolutely not,” Tucker testified.

Buckner said he wasn’t “very good with financial or legal matters” and didn’t understand “how much money was involved.”

The property had a tax value of $110,000, no mortgage, and, according to a document publicly available in the court file, was under contract for $148,000 as of October 2020, more than a month before Buckner signed the deed.

Tucker did not respond to questions from Asheville Watchdog about when he knew the sale price.

James Kilbourne, an Asheville attorney, was appointed to represent Buckner. At a second hearing in September, Kilbourne called the sale an “extreme situation.”

“It’s not as if they offered him $90,000 for a $150,000 house,” he said. “They offered him $10,000.”

Tucker had knowledge of the legal system and access to information about the property that Buckner, in prison in Florida, did not, Kilbourne said. He told Buncombe Superior Court Judge Steve Warren, “You don’t need our client to testify that he got snookered to know he got snookered.”

Judge Warren ruled that the property had been turned over to the estate at the time Buckner signed the deed; therefore it wasn’t Buckner’s to sell, and Asheville Holdings had no legal interest in it. Buckner stood to receive the $136,000 from the sale of his father’s house, but in October Tucker’s company filed a notice to appeal the judge’s ruling.

‘No deal,’ a daughter intervenes

Barbara Warren already knew Lisa Roberts from church and assumed she had her best interests at heart when she signed over her house across from McCormick Field in downtown Asheville to a Tucker company, said her daughter, Pamela, of Charlotte. The purchase price was 59 percent of the property’s tax value. Warren at the time was 76 and, according to a letter from her attorney, William Biggers, “confused about the consequences of her actions.”

Under the arrangement, Warren would lend Tucker’s company the $88,510 she was due, and his company would repay her $5,000 a month, interest-free, according to documents provided by Warren’s family. Warren wouldn’t receive all her money for up to 18 months but would have to leave her house within six months.

Warren also signed a “disclosure” acknowledging that Tucker was an attorney and that she could have sought legal advice but had “chosen to represent myself.”

In an interview with Asheville Watchdog, Warren’s daughter said she learned of the sale in a phone call from Lisa Roberts.

“I said, ‘No deal, no deal,’ ” Pamela Warren said. “ ‘First of all, Lisa, you know, Mom is legally blind.’ ” Pamela Warren drove to Asheville and with Biggers’s help got Tucker’s company to deed her mom’s house back.

“I think [Barbara Warren] was being taken advantage of,” Biggers told Asheville Watchdog. “She’s had a tough life and just probably was very vulnerable to something like that.”

Henry said he was unfamiliar with the case. “I can’t tell you whether any of these deals are good deals, bad deals or anything,” he said. “That’s in the eye of the beholder.”

Asheville-area investors exploit Jim Crow-era law

Five hundred dollars was all it took for Robert Perry Tucker II to gain an interest in an Asheville home that had been owned by a Black family since 1918.

Two elderly heirs signed deeds selling their shares of the home to a Tucker company for $250 apiece. With their ownership in hand, Tucker’s company used a Reconstruction-era law to force a sale of the entire property, and another Tucker company bought it at auction for $3,750.

The eight heirs whose family had owned the property for a century received $445 each, the auction commissioner reported. The Tucker company that bought the property sold it in three months for $55,000.

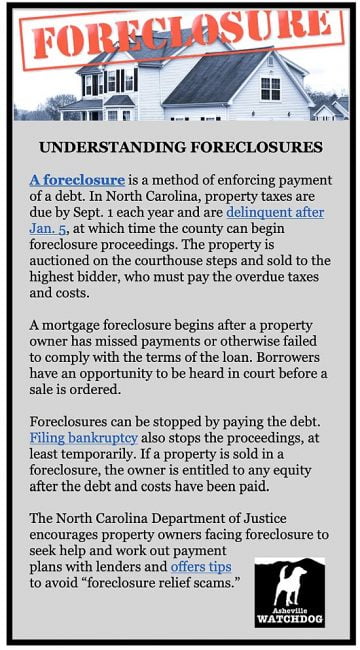

The law enabling the sale, known as partition and sometimes called “forced sale,” allows any co-owner in a jointly owned property to cash out their share by requesting local courts to physically divide the property or sell it and split the proceeds. Partitions are meant to resolve disputes among family members or business partners, but the law has been exploited by investors who acquire one or more relatives’ interest—however small—force a sale, and buy the entire property, an Asheville Watchdog investigation found. When sold by public auction, partition sales typically bring prices substantially below market value.

Low-income owners and minorities are especially vulnerable to exploitation when they inherit property from a family member who died, usually without a will, in what is known as heirs’ property. Partition sales have become a major source of land and wealth loss, particularly in the South among Black families, where such property is a common form of ownership that in some cases traces to Emancipation.

Tucker’s companies have filed at least a dozen partition actions in Buncombe County since 2015, Asheville Watchdog found in a year-long investigation that involved reviewing scores of real estate transactions and court filings, and more than 100 interviews.

Tucker’s attorney, Peter R. Henry of Arden, points out that partition actions are “completely legal.” Lawyer groups, including the real estate section of the American Bar Association, call partitions potentially exploitative and have endorsed a uniform law that helps preserve families’ property wealth. Nineteen states have passed it. North Carolina is not one of them.

Investor buys half of West Asheville house

For $3,000, a Tucker company bought a half-interest in Kathy Waites’s West Asheville home, assessed at $303,800, and is now seeking to force a partition sale of the house where Waites has lived for 10 years and had hoped to spend her retirement.

“I don’t know where I’m going to go or what I’m going to do,” said Waites, 62.

Waites filed a lawsuit in October 2020 accusing Tucker and his company of fraud by acquiring her nephew’s share in the property through “false representations,” including that he could go to jail for unpaid property taxes. In answer to the suit, Tucker and his company denied wrongdoing.

Asheville Watchdog previously reported how Tucker’s companies have acquired properties, often in foreclosure and estate cases, at far below market value. Of more than four dozen transactions reviewed, nearly half the sellers were Black, even though Blacks make up just 3.9 percent of Buncombe County homeowners.

Lisa K. Roberts, a Black woman who calls herself a housing advocate, negotiated some of the deals and has notarized documents in at least 20 transactions to Tucker’s companies since 2013, the majority from Black sellers.

Roberts, who also goes by Roberts-Allen, declined to speak with Asheville Watchdog, despite repeated requests. Tucker referred questions to his lawyer, Henry, who described all of the transactions as voluntary and legal.

“Terrifying and heartbreaking”

Waites’s house has been in her family since 1935. She owns half, and after her brother’s death, the other half passed to her now estranged nephew, Linsey Waites of Georgia.

Kathy Waites paid all the expenses on the property but missed two years of property tax payments after her income declined due to a health issue.

In 2019, Buncombe County began tax foreclosure proceedings. Linsey, 28, didn’t like being served with a court summons at his job at a food processing plant, he said, and sold his half interest to a Tucker company for $3,000. A “memorandum of conveyance” recorded with the deed is notarized by Lisa Roberts.

The property had a tax value of $229,600 and a Zillow estimate of $308,000, making Linsey Waites’s interest worth at least $114,800.

The property had a tax value of $229,600 and a Zillow estimate of $308,000, making Linsey Waites’s interest worth at least $114,800.

The sale price is “so disproportionate to the value … it would shock the conscience of a reasonable person,” said Kathy Waites’s lawsuit, filed by attorney Martha Bradley.

In an interview with Asheville Watchdog, Linsey Waites said Tucker told him that he “was going to have to pay” his aunt’s taxes, but if he signed over ownership, he’d “be clear.”

Linsey Waites said he didn’t want the house anyway, had never lived in it and didn’t even know he owned half until he began receiving notices for overdue taxes. He said his mother, Mary, of Asheville, who had been married to Kathy Waites’s brother, worked out details of the sale.

Mary Waites told Asheville Watchdog a woman called her several times and came to her house, presenting herself as an “advocate” and telling her that Linsey could be responsible not just for his aunt’s property taxes but her other bills, too. Mary Waites could not recall the woman’s name or provide a description.

The woman showed her paperwork of Kathy Waites’s credit card debt from Bank of America—a collection action against Waites for $13,562 had recently been filed in court—and said “there’s more to be coming out,” Mary Waites said.

The woman said “they’d chase” Linsey and that “it would all be his responsibility to pay back,” Mary Waites said. “He didn’t have no money to pay it … Linsey ain’t got two cents.”

The woman said he could be tied up in court or worse, an implication Mary Waites said she took to mean that her son, who had an arrest record, could go to jail.

“He could be liable,” Mary Waites said. “He could go to court, all drawn out, whatever, you know, left that up to your mind, you know what I’m saying?”

Asked if she feared her son could be locked up over his aunt’s debts, she said, “Hell, yes, I was worried about it because if he didn’t have no money to pay nothing, what was left to happen?”

Property owners cannot be jailed for failing to pay property taxes in North Carolina, and Linsey Waites would not have been responsible for his aunt’s debts. Had the house been sold in a tax foreclosure, the proceeds after taxes and fees would have been split between Kathy and Linsey Waites.

“If we had known that, we wouldn’t have done that,” Mary Waites said. “It was just about getting Linsey out of trouble.”

No money was mentioned until right before the deed signing, she said. The initial discussions were “just to help us get out of the situation.”

Mary Waites said she insisted on being present when her son signed the sale documents, and a man Linsey identified as Tucker drove her to Georgia. Linsey received $3,000 and Mary, $1,000, both in cash, Mary Waites said.

She said she now realizes Tucker’s company got Linsey’s interest for “goddamn nothing” but that she’s relieved her son is “out of it.”

In a response to the lawsuit, Henry said that “no fraud or misrepresentation took place” and asked the judge for a partition order forcing the sale of the property.

Courts often order partition sales by public auction, and owners who want to keep their property must bid against the investor.

Kathy Waites filed for bankruptcy last year and said she has no money to outbid Tucker if her property goes to a partition auction, a prospect she finds frightening.

“I’ve been very independent all of my life, and this has been humbling and terrifying and heartbreaking,” she said.

To be continued…

Read Part I: Equity Erased – Real estate deals strip elderly and poor people of their homes, land, and inheritances.

Read Part III: Equity Erased – NC’s Partition Law Easily Exploited.

Read Part IV: Equity Erased: Exploiting the Partition System and Property Owners.

Read Part V: Equity Erased: Buncombe Homeowners Forfeit Years of Equity.

Asheville Watchdog is a nonprofit news team producing stories that matter to Asheville and Buncombe County. Sally Kestin is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative reporter. Becky Tin is a retired district court judge and lawyer. Email [email protected].

Asheville Watchdog is a nonprofit news team producing stories that matter to Asheville and Buncombe County. Sally Kestin is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative reporter. Becky Tin is a retired district court judge and lawyer. Email [email protected].

Asheville Watchdog gratefully acknowledges the assistance of Lawyers for Reporters, a joint project of the Cyrus R. Vance Center for International Justice and the Press Freedom Defense Fund, and the Duke University School of Law’s First Amendment Clinic, with special thanks to Jonathan Ellison, Danielle Siegel, and Zane Martin.