Book Bag – March 2015

Women’s Stories of Re-invention and Revolt from Around the World

reviews by Sharon L. Shervington

Women’s History Month is a time to tell women’s stories, and there is a particularly large selection this March.

Consistent contributions to historical fiction over the last several years have led to devoted followings for Michelle Moran and Kate Quinn. Both have eagerly awaited new releases out this month.

In Lady of the Eternal City, Quinn delivers a compelling fourth entry to her “Empress of Rome” series, this time focusing on Emperor Hadrian and his consort, Vibia Sabina. Hadrian’s reign was considered part of a golden age for Rome, and yet he was known as a paranoid and vindictive brooder who could hold a grudge until the end of time.

His complex relationship with Sabina, whom he married primarily for her imperial connections, is depicted here along with his devotion to the man, Antinous, who was the love of his life. Although homosexual relationships in youth were accepted in Roman culture, the length and depth of the bond between the two caused extraordinary pressure on the imperial family. And because so much of our society is based on ancient Greek and Roman thought, this is a read that is provocative on many levels.

Secrets and deception, and of course the role of women, are among the book’s entertaining main themes, but it is Empress Sabina’s own secrets involving half-Jewish Vix—a warrior she has known since childhood—as well as her sister’s children, that also helps drive the action. This is a sequel to Empress of the Seven Hills. (Berkley; $16; 519 pages)

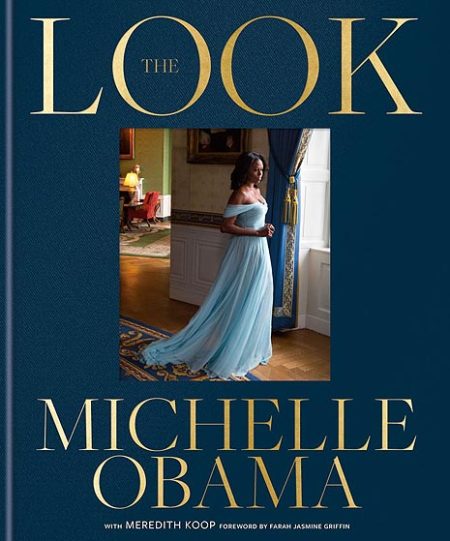

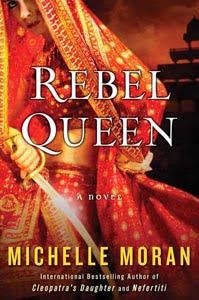

Michelle Moran has always been extraordinarily adept at piecing together women’s individual and collective struggles across centuries and telling their stories. Her subjects tend to the larger than life: the queens of ancient Egypt, for example, or Madame Tussaud, whose family founded the world-renowned waxworks.

In Rebel Queen she continues building an exceptional body of highly original work, telling the story of Rani Lakshmi, ruler of the kingdom of Jhansi, one of two or three of India’s best-known women. It is her story as well as that of a leader of her elite personal guard, whose members were trained from childhood in all sorts of weaponry and such other skills as language, poetry, and philosophy.

The guard, Sita, comes from a rural family and village that practice customs like purdah. When Sita is selected for the highly competitive post, she begins to experience the world fully for the first time. And when the British try to take over the country, she serves the stoic and brilliant rani in many capacities, among them warrior and diplomat, traveling to England with a personal appeal to Queen Victoria.

The British East India Company, and its important role in the history of corporations as we know them today, also is explored. Though this is a novel it corrects common assumptions about the history of the British Empire, providing a good basis for better understanding the struggles of the Indian subcontinent for self-determination as well as market forces that continue to shape the world as we experience it today. (Touchstone; $26; 355 pages)

Newer to the scene is Patricia Bracewell, who nonetheless delivers the well-worth-waiting-for The Price of Blood, a sequel to her well-received Shadow on the Crown. These novels are set in grim times indeed: England in the early 11th century, when the country was attempting to repel sequential invasions from well-equipped Viking hordes.

Shakespearean elements abound with King Aethelred, worthy of comparisons to Macbeth and even Lear. Of course, he would be well worth disliking for his woman-hatred alone, but the fact that his actions against the truly good and wise Queen Emma endanger the entire kingdom adds another layer to this villain’s repellent character. Not only does the king project his guilt over his brother’s death onto all those who might love him, but he abuses and uses his spouses and children as if they were pieces on a game board.

Several well-drawn supporting characters, notably the wealthy, scheming Elgiva, and the king’s first-born son Aethelstan, add verve to this sometimes tragic tale. Appropriately enough for a historical novel set during Britain’s early years, The Price of Blood ends with a sharply written cliffhanger. (Viking; $28.95; 426 pages)

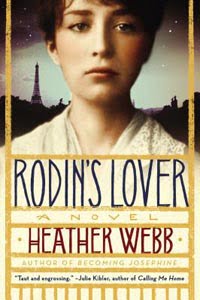

Another writer to watch in this genre is Heather Webb, whose first novel Becoming Josephine concerned Napoleon’s first wife, Marie-Joseph-Rose de Tascher de la Pagerie, a native of Martinique. In her new book, Rodin’s Lover, she tackles Camille Claudel, the well-known sculptor who spent the bulk of her later life in a mental institution. She was the muse and lover of Auguste Rodin at a time when women’s lives were much more strictly controlled than today.

The elements of her tragic love and life have been covered before, but what is fresh here is the rotation of points of view throughout the narrative and the inclusion of notables of the time like Debussy and Zola. And it is more than sympathetic to her brother Paul (the religious poet) and her mother, who, had she lived today, might well have been diagnosed with mental illness herself. In its own way this is a meditation on mental illness that still is relevant. This is a streamlined account of a complex life. (Plume; $15; 307 pages)

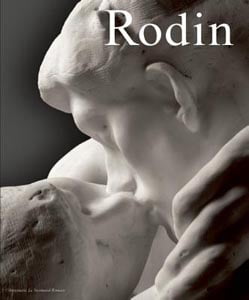

For those who may want to learn more about Claudel’s life and legacy, I recommend Rodin, an artist monograph by Antoinette Le Normand-Romain, a lavishly illustrated and researched (drawings, photographs and other documents are all here) art book that puts the pioneering nature of his work and times into clear perspective. And in the process she shares important insights into Claudel’s work and her effect on him. The author’s passion for her subject jumps out from every page. (Abbeville Press; $150; 432 pages)

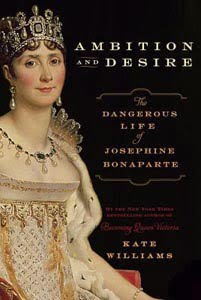

On the nonfiction side, Ambition and Desire: the Dangerous Life of Josephine Bonaparte is engrossing. It explores the material excesses of the monarchy and of the French Revolution, a good bit of the latter which Josephine spent in a prison cell. It also explores the ways in which life was a prison for so many women of the time; women who, even in the wake of revolution had virtually no choice but to marry or take the veil. In fact, as Napoleon came to power, financial and marital rights and privileges which women had once enjoyed were revoked, something that hit the empress hard when she was unable to provide him with an heir.

There is a good bit of fascinating history regarding her early life and first marriage to wealthy wastrel Alexandre as well. Wonderful photographs accompany the text. (By Kate Williams; Ballantine; $30; 387 pages)