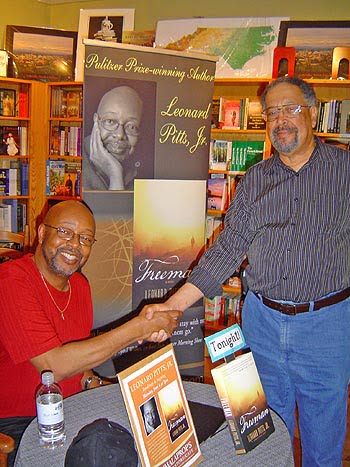

Freeman written by Leonard Pitts

|

| Fred Simms, board member of Building Bridges-Asheville, greets Pulitzer Prize winning author Leonard Pitts during his book signing event at Malaprops Bookstore. Photo: Urban News |

reviewed by Sharon L. Shervington

Over the last three years I have had the pleasure of reviewing several books on slavery, both its existence and aftermath, in the Americas and the Caribbean, including Isabel Allende’s Island Beneath the Sea and Andrea Levy’s The Long Song. But I think Leonard Pitts’s Freeman is my favorite. It will enthrall all readers who love character-driven works and who prefer substance (and sometimes brevity) over some of the wordy tomes that are a staple these days, especially at this time of year.

The writing is supple and smooth without a lot of padding, possibly due to the fact that Mr. Pitts – as a nationally syndicated columnist – is required to write two columns a week to meet specific word limits.

All these books encompass to some extent the casual – and horrific – violence of slavery, showing it for what it is: the theft, by violence, of the labor of one group by another group. Freeman explores the conditions under which the slaves lived and the paradox that laws ostensibly created to build a more fair world were used instead to do exactly the opposite.

The story takes place in the days and weeks after the end of the Civil War, with Lincoln’s assassination happening early in the book. The lead character is Sam Freeman, a former slave residing in Philadelphia, working in a library among the books he loves so much. He believes that his articulate nature, erudition, and dignified carriage will be enough to protect him from harm. And on that score he gets a very rude awakening.

When the war ends Sam has an overwhelming urge to seek out the wife he was forced to leave behind in Mississippi. Tilda is beautiful and literate, and the mother of his only son. Sam has a bond with her that can never be broken, and he is determined to find her – even if that means walking a thousand miles, even if he dies trying.

Of course he has no guarantee that she will still be on the plantation where she worked and where her mistress was a virtuous woman, for a slaveholder; she prohibited whippings, kept families together, and even encouraged literacy. Nor does his naïve self-confidence serve him well; luckily he falls in with Ben who, though illiterate, knows the ways of whites and their hatreds and saves Sam’s life.

Their individual story is embedded in a larger one, the overwhelming particulars of which will never be known. Because the practice of separating families from each other had gone on so long, millions never found their wives, husbands, sons, daughters, or grandparents. And even though slave marriages had no legal standing, they were marital bonds nonetheless. (If you are a parent this book will hit you especially hard, because to lose a child for any reason is the worst nightmare of any loving parent.)

Freeman reminds us of what it really meant for hundreds of thousands of women to be separated from the babes they nurtured in their wombs – their children taken from them and sold for personal gain. And yet despite the tragic elements, especially families being torn apart, this story is still full of hope.

Pitts deftly evokes one profound source of hope, one vehemently denied most blacks: literacy. Education was and is a key component of freedom – both personal and political – and it is education that brings us to the book’s other protagonist.

Prudence Cafferty Kent, is a wealthy young woman from Boston’s Back Bay who, in the heady days following emancipation, decides to go to Mississippi, where her father owned property and slaves, and start a school for “colored” children. She is accompanied by Bonnie, her black sister who has been raised as one of the family’s four girls. Bonnie displays a poise, elegance, and erudition that whites seem unable to fathom – and her character shows how often blacks were forced to lie about who and what they were to survive. Still the book has its fair share of humor, and the response to Bonnie and Prudence as they travel is at times truly comical.

With good reason Bonnie is frightened for both Prudence and for herself, having a better sense of the bitter task they are taking on. Prudence is known to be brilliant and headstrong and, like Freeman, more than a little naïve. When the pair arrive in Buford, they face a visceral and eventually deadly hatred from the powerful whites, who are furious at the idea of “their niggers” being educated.

Sam and Prudence meet when they are at their lowest ebb. Sam has been shot, stabbed, stomped, and beaten, and lost an arm on his journey, and the scenes in which Prudence attempts to nurse him back to health are among the most sensitive and moving of the book.

Surrounding these central elements of the plot are other characters: a group of men who guard the school after it is vandalized, the wise Ginny Campbell, and a slave of the county’s wealthiest and most powerful family who shyly tells Prudence that her name is Colindy. The whites, she says, insist on calling her Sassafras, or Sass for short. This issue of naming is crucial in terms both of an individual’s self-definition and of subjugation by a master.

In the end, Sam’s fears that he will be unable to find Tilda are well-founded: she has been sold to a vicious wretch of a man, and years of his hatred and violence have taken a terrible toll on her. Interestingly, Freeman shows us the unique role that black newspapers sometimes played in reuniting families and other lost ones.

This is a wonderful book, a multi-layered novel that can and should be savored on many levels (it is also deliciously erudite, with quotes from Diderot, Cervantes, and others). Put yourself in the hands of this master storyteller, as I did, and allow the surprises and magic to unfold.

Freeman by Leonard Pitts; Bolden Books; $16; 401 pages