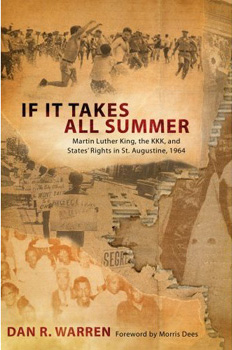

If It Takes All Summer: Martin Luther King, the KKK, and States’ Rights in St. Augustine, 1964

Written by Dan R. Warren, foreword by Morris Dees.

Written by Dan R. Warren, foreword by Morris Dees.

Published by the University of Alabama Press, 2008, 210 pages.

Book review by David L. Swain

In his engaging book, “If It Takes All Summer,” author Dan R. Warren recounts the mounting rage within society against racial discrimination, and how he, as a middleman appointed by the governor of Florida, worked within a difficult racial situation in St. Augustine, Florida, to bring inescapable reason and a gutsy morality into the super-heated situation of the summer of 1964.

Founded in 1564 by the Spanish admiral Pedro Menendez de Aviles, the city in 1964 was preparing for its quadricentennial celebration. There was one fatal flaw in the arrangements: no black citizens were included in the planning.

This deliberate exclusion of a major segment of the city’s citizens

doomed the celebration from the start. And that failure impelled Dr.

Martin Luther King, Jr., and his supporters to come (as uninvited

guests) determined to end segregation there. It would also bring the Ku

Klux Klan to the nation’s oldest city. Dan R. Warren, the District

Attorney for north Florida, knew the Klan would be more welcomed by

white citizens than King would.

So, as the city prepared to celebrate its 400th birthday, with

Vice-president Lyndon Johnson scheduled to deliver the keynote address,

no blacks were invited to attend (though Johnson had made it clear that

he would not attend if blacks were left out). But the exclusion of

African Americans brought not only Dr. King but also leaders of the

Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to the city, and it

stirred into action the local NAACP chapter, which saw clearly that the

community as a whole was not satisfied with segregation, and thus

sought to make the necessary changes. These leaders produced a report

that judged civil rights conditions in St. Augustine to be

“considerably worse than in most if not all other cities in the state.”

The civil rights proponents faced a group of equally committed

racists, led by Sheriff L. O. Davis and his friend Holstead Manucy,

local leader of the Ku Klux Klan and head of St. Augustine’s Ancient

City Gun Club, which boasted many Klan members.

The real power of the Klan was centered in three men: J. B.

Stoner, an Atlanta lawyer, who believed segregation was essential to

the security of whites; Connie Lynch, a master at fomenting hate; and

Manucy, “a pot-bellied farmer and convicted moon-shiner.” Forida

governor Farris Bryant refused to interfere or even cooperate with the

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, claiming the crisis was purely local.

That February (1964), the Civil Rights Act had passed in the

House of Representatives by a vote of 290 to 130. Strong support for

the Act came from Mabel Norris Chesley, associate editor of the Daytona

Beach “News-Journal,” from its managing editor, Tippen Davidson, and

from a lawyer named George Allen.

Meanwhile, black citizens marched in the city’s streets during

daytime. Besides support from Martin Luther King, they were joined by

such well-known persons as Jackie Robinson, Sarah Patton Boyles, wife

of a University of Virginia professor, and William England, a chaplain

at Boston University, among others. Local church leaders remained

silent.

In the end, though, District Attorney Warren won, and for his

efforts was invited to speak in February 1965 to the combined faculties

of law and theology of Boston University, where Dr. King had earned his

doctorate of theology.

Warren’s lecture stressed the key lesson

of the struggle in St. Augustine: the racial struggle in St. Augustine

and its resolution by ethically motivated persons in the churches, the

courts, the public media and schools, and elsewhere underscored a basic

truth of the evil that can happen when good people of conscience fail

to act.

That it took nearly two hundred years for blacks to obtain the

same rights enjoyed by the original patriots demonstrates this truth so

painfully. Or as the Jewish philosopher put it: “The opposite of faith

is not heresy; it’s indifference. And the opposite of life is not

death; it’s indifference.” Warren sums it up thusly: “It was

indifference (on the part of politicians, community leaders, churchmen,

ordinary men and women (that allowed the Klan to step into the

limelight and carry out its agenda of hate and brutality.”

And that brings us to the final words of Warren’s book, namely,

Edmund Burke’s dictum: “The only thing necessary for the triumph of

evil is for good men to do nothing.”