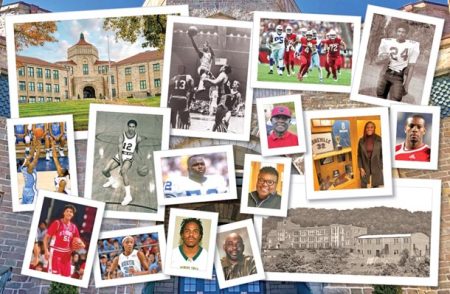

What Ever Happened to Asheville’s African American Community?

By Willie Cameron, Jr.

What’s called “The Block” is scheduled for a facelift, something that has taken more than 20 years to come to fruition. In the meantime, local landmarks that tell the visual history of the black community in this city have disappeared or become places to be used by Asheville 2014 with little, if any, thought to their historical significance.

I grew up in Asheville in the era when Stephens-Lee High School was both admired and aspired to. What is left of that structure is now a community center. Lee H. Edwards (which I attended), still flourishes as Asheville High School.

Mountain Street Elementary, which served the East End/North Side African American communities until the 1957 Supreme Court ruling on segregation came down, was replaced by a brand-new building back in the mid-1960s. The Mountain Street building was renamed Lucy Herring in honor of a local black educator and now houses the administrative offices of the Asheville City School System.

The Hill Street School was erected during the same time period as a number of other schools here in the city, one being Claxton Elementary in North Asheville. In the late 1980s or early ’90s, Hill St. was renamed Isaac Dickson, in honor of an early 20th-century leader of the black community.

Many a native black Asheville baby boomer attended this school on their way to the mighty Stephens-Lee High. Late last year the building was demolished to make way for a new state-of-the-art school. But Claxton was given a renovation facelift, and designated the school for the humanities and arts.

Soul food, such things as fried chicken, fish, fatback and greens, and yes, even chittlins, was what the old Rabbit’s Restaurant on McDowell Ave. specialized in. The juke box belted tunes from Al Green; Earth, Wind & Fire; and The Temptations. The TV played sports or Oprah. Conversation was lively, and laughter plentiful; it was a place where being black was not a bad thing. That business closed and has not been replaced by a new one of that same genre.

Thirty years ago when my wife and I were dating we enjoyed our weekends together dancing the night away to the music of Harry (Harry Hippy) McLaughlin at such places as Stephens-Lee Center, the Senior Opportunity Center, Blackwell’s Lounge, Broadway Club, and the Greek Center. Today from time to time I ask young African Americans where do they go to party, and more often than not the answer comes back, “Out of town.”

I have no scientifically proven reasons for the situations I have just described, but I do have some rationally thought out theories.

What first comes to mind is the city’s demography. The percentage of blacks in this community hovers around 12% where it has been so for many years. However, many of the people included in that 12% come to live here from other places and therefore have very little knowledge or respect for the black history of the town. People, places, and things that mean a great deal to natives do not hold the same value to them. Thus saving these things is not a high priority.

Since the end of World War II, Asheville blacks as well as other African Americans came to view education as the road to upward mobility for their children. Every year our local high schools graduate the portion of black youth described by Dr. W.E.B. Dubois as “The Talented Tenth.”

These young people leave to attend colleges and universities in this state and others, and on the whole, these intelligent youth never come back to live in Asheville, taking their talents and intellect to other communities. Asheville never benefits, but being African American I can’t blame them either. And of course the military claims its share.

These and other problems in black Asheville cannot be solved by politics. Just like the ESPN TV show, Numbers Never Lie tells us it would be impossible. Sure, we had a female black mayor; however, that historical feat was accomplished by a coalition with the majority. Only 6% of black registered voters in Buncombe County even bothered to vote in the last election, and because of such issues as gay rights, these voters wandered to each side of the political spectrum. There is no such thing as a black voting bloc anymore.

The only institution that might make some change in this community is the black church. She has the influence, the property, and some of the capital to make a difference. In this day and time, however, the church has its own problems to contend with.

Church membership is falling significantly. Old members pass away, and unlike days gone by, are not being replaced by the next generation. People do not value church like in the past. Those who do are torn because it seems that church is an oligarchy benefitting a few at the expense of the many. Solve these problems, come together regardless of denomination, and the local black community will rise.

When family members come to visit me from other towns they always ask the same question, “Where are the black people?” I say, “I know where four are. Three are at work and one is retired living the life of Riley.”