Does the YMI Cultural Center Face a Questionable Future?

|

| The official incorporation of the Young Men’s Institute took place on May 8, 1906, making it among the earliest, if not the oldest, black cultural centers in the country. |

by Johnnie Grant

Photo: Renato Rotolo

The YMI Cultural Center has served as the hub and center of black life in Asheville for more than a century. It has reflected, guided, and in many respects shaped the historical and cultural legacy of African Americans throughout Western North Carolina, making it by far the most significant focal point of black history in the region.

The impetus for its existence is believed to have come from the Jamaican-born Professor Edward L. Stephens, who served as principal of Catholic Hill School, the city’s first public school for black children. He learned that George W. Vanderbilt had refused to follow the custom of segregating his workers by race when he built his Asheville home, Biltmore House, and he prevailed on the tycoon to establish an institution in Asheville “for the convenience and service of colored men and boys.”

A Distinguished History

Construction of the YMI began in 1892 under the supervision of

architect Richard Sharp Smith, who was born in Yorkshire England in

1852. Smith migrated to America at the age of 20 and began working in

New York, where he later was employed by the architectural firm of Hunt

and Hunt. Architect Richard Morris Hunt, who designed Biltmore House

(which opened in 1895) and All Souls Cathedral in Biltmore Village

(completed in 1896) sent Smith to Asheville as the resident supervising

architect for the YMI.

Smith built many buildings throughout the city of Asheville, including

the Masonic Temple on Broadway, the Oates Building, St. Mary’s Episcopal

Church, the Legal Building on Pack Square, as well as a number of

private homes. His correspondence with Charles McNamee, Vanderbilt’s

legal counsel, provides evidence that both men paid meticulous attention

to detail in the construction. Only the best materials were to be used,

and the top-quality pebbledash façade of the building, as well as the

paving, was done by Wesley E. Wolfe, uncle of author Thomas Wolfe.

A Remarkable Feat

A dozen years after it opened, a group of 41 black men—undertakers and

educators, business owners, doctors, and others—raised $10,001 and

bought the building from Vanderbilt; from then on, Asheville’s black

residents not only had a home, but owned it as well.

The opportunity to manage and run a center like this was unheard of

among African American communities in 1905, especially in Southern

Appalachia. Its establishment was a remarkable feat, its success even

more so.

The official incorporation of the Young Men’s Institute took place on

May 8, 1906, making it among the earliest, if not the oldest, black

cultural centers in the country. Its incorporation announced the mission

and purpose of the YMI to “establish and assist in the spiritual,

mental, social, and physical well-being of the Negro people of Asheville

and vicinity, and as a literary organization.”

The Heart of the Community

“If the walls of the YMI Cultural Center could talk, they would tell

the story of truth and history of the region’s African American people,”

says Lucille Flack Ray, a local African American historian, author, and

Asheville native. “They would pretty much tell you about what’s going

on now. All you have to do is go to the building—go in and look and

listen!”

The YMI was created as an economic model of self-sufficiency, with

street-level stores spurring community development and the rent they

paid helping pay down the debt on the building. Mrs. Ray fondly

remembers the YMI’s pivotal role in shaping people’s lives in the

African American communities of Asheville and the surrounding region

during her childhood. Throughout much of the 20th and into the 21st

century, the building housed shops, guest rooms, meeting rooms, and

played host to a wide variety of community functions.

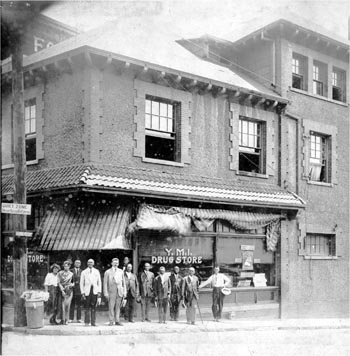

Medical and dental offices, a barbershop, and an apothecary/drug store

met community needs, as did a reading room and ladies’ sewing room. The

Institute provided adult night school classes, a day school and

kindergarten, a Sunday school, a Masonic lodge, a large assembly hall,

and a basement gymnasium with swimming pool, as well as sleeping rooms

for visitors denied accommodation in the city’s segregated hotels.

The North Carolina Mutual Insurance Company had offices in the

building, and for more than three decades the YMI housed the ‘colored’

branch of the Buncombe County Library system.

“From 1929 through 1961, the Market Street Branch Library was

identified as the “Colored Public Library.” The ‘Whites Only’ Pack

Memorial Library was around the corner in what is now the Asheville Art

Museum,” said David Miles, Asheville Middle School assistant principal

and co-chair of the ASCORE Youth Leadership Committee, which earlier

this fall commemorated the 1961 desegregation of the library system.

Church congregations also met in the YMI building, as some still do

today, and many local congregations hosted musical events at the YMI

that grew to become popular public social events. Much like a rite of

passage, the social and enrichment programming hosted by the YMI during

its earlier years helped shape the lives of African Americans from

throughout the region.

Turbulent Times

For its first 30 years the YMI flourished as an entirely independent

organization, led by the dedicated General Secretary Fenton H. Harris

and enthusiastically supported by the local African American community.

Then the Great Depression took its toll, and for a brief period the

building closed and fell into disrepair. Although the Institute reopened

in 1930, World War II and a lack of money kept it largely inactive

throughout the 1930s and the war years.

On March 24, 1944 a reorganization meeting was held in the community to

determine the organization’s future. On March 25, 1945, under the

leadership of Dr. Robert M. Hendrick, the YMI reopened with another of

the popular Sunday afternoon song services. That reorganization, which

was not to last long, was the first of several over the decades to come.

In 1946 the building was sold to the Market Street Branch YMCA, and for

the next few decades the YMI remained under white management, though it

still functioned as a primary recreational facility for the black

community.

The black neighborhood centered on The Block declined during the 1960s,

as desegregation and the first wave of “Urban Renewal” destroyed area

homes and prompted businesses to relocate, decimating the community. By

the mid-1970s the YMI had fallen on hard times, and once again it was

not clear that it would survive. In 1976 the Market Street Y closed, and

in 1977, despite its inclusion on the National Register of Historic

Places, the YMI building was condemned.

That ominous future spurred the African American community to regain

ownership and control of the Institute, led by representatives from the

nine African American churches that operated Asheville’s Friendship

Nursing Home. The organization’s board soon voted to change its name to

the YMI Cultural Center, Inc., and in September 1980, after a strenuous

but successful fundraising effort, the group purchased the building and

began the arduous process of renovating the historic structure.

One of the first major programs designed to raise the organization’s

profile in the community (and raise funds) was the Goombay! Festival

started in 1982 by Friends of the YMI. The women who led the

effort—sorority alumna who had traveled to Florida for a convention—had

happened upon a Caribbean-style Goombay festival there and decided to

replicate it in Asheville. That same year (1982) the revitalized YMICC

received the Stedman Incentive Award from the Historic Preservation

Society of North Carolina.

Renovations were completed in 1988. After the YMI joined Pack Place,

additional renovations were undertaken, and for several years, while the

Stephens-Lee Gymnasium was being refurbished, the YMI also served as a

facility of the Asheville Parks & Recreation Department. In 2003 an

elevator was added, making the building accessible to the disabled.

Where Next?

Since its rebirth in the 1980s, the YMI has been a significant cultural

repository for black history in Asheville and Western North Carolina.

It has used grant funding to support historic research projects,

cultural programs for the public and area schools, and art exhibits

showcasing the wide variety of both nationally renowned and locally

based minority artists. Its collections and historical exhibits reflect

the history of African Americans and other minorities in Western North

Carolina, and its outreach programs have helped educate thousands of the

region’s students about black history and culture.

Each incarnation of the YMI has lasted approximately one generation:

from 1906 to 1929, from 1946 to 1979, and from 1980 to today; where the

YMI will go next is yet to be determined. Lacking a full-time Executive

Director for more than a year, and with few public events on its

schedule to draw in members and the public, many in the community have

expressed worry that the historic center is facing another crisis over

its future.

Community members have begun yet another campaign to come to the aid of

the YMI Cultural Center by sponsoring membership drives throughout the

region. Membership is $50 per year.