Book Bag: Integrated Thinking: The Importance of Being Eugene is in the Stories

|

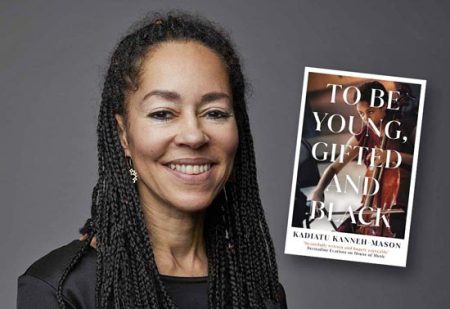

| Eugene Robinson Image courtesy of Doubleday |

By Sharon Shervington

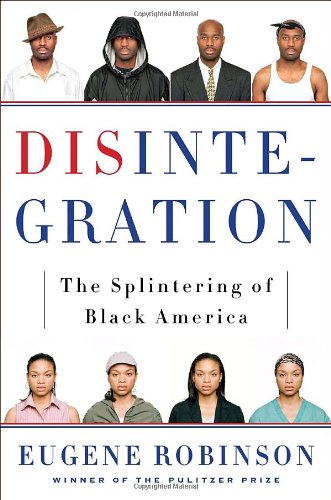

Having grown up in the 1950s and 1960s in Orangeburg, South Carolina, Eugene Robinson remembers both the routine humiliations of segregation and the process of integration. As he discusses in his book Disintegration: The Splintering of Black America, his is the first generation of African Americans to really make it big on the world stage and to get beyond Jim Crow.

Of course, there had been generations of blacks with big talent, particularly in the area of arts and letters, who had to go abroad for recognition, and that, in turn, heavily influenced the prevailing cultural narrative.

That and the fact that until the 1970s, in the aftermath of the riots and the Kerner Commission report, few blacks were employed in mainstream journalism and even fewer as cultural critics or with the authority of deciding whose stories would be told.

As an enduring star in the world of journalism, with a range of

high-ranking posts from Bureau Chief in London and South America to

Foreign Editor and Style Editor, all at The Washington Post, Mr.

Robinson has earned his place as a luminary on the world stage.

Between those posts, his work as a syndicated columnist for the past few

years, his frequent television appearances, and his well-received

efforts as a book author, Mr. Robinson has told countless stories. (In

addition to Disintegration he has written Coal to Cream and Last Dance

in Havana, also dealing primarily with issues of race, class, and

culture.) In December, he was appointed to the Pulitzer Prize board, a

scant year after winning the Pulitzer Prize himself.

This book is thus a kind of capstone for one very hot year. But it also

This book is thus a kind of capstone for one very hot year. But it also

reflects the accumulated knowledge of more than 30 years in journalism

during a period when the country went from the aftermath of Jim Crow to

the solid and symbolic victory of a first black president, with African

American reporters actually covering the story.

Still, as the author makes clear: While society is much improved, it is

far from “post-racial.” By weaving together traditional elements of the

African-American experience with others that will be less well known,

especially to white people, Mr. Robinson creates an insightful whole

that segues from the past well into the future, and yet is firmly

grounded in the present.

His thesis is essentially that blacks are no longer a monolithic culture

that has often held sway in the national consciousness. Today, instead,

African Americans comprise four groups: the Mainstream; the Abandoned;

the Transcendent (people like Oprah, Tiger Woods, Robert L. Johnson,

etc.) and a double group, the Emergents, combining immigrants from

Africa and the Caribbean with mixed-race people. And the groups, in many

cases overlap so that the analysis is in no way cut and dried.

Combining the authentic voice and the chops that have made him so

popular, with the necessary context (so often ignored in the current

media climate), Mr. Robinson has crafted a series of interlocking

narratives that make sense of where we are now and how we got there. To

see what a dab hand he is at choosing and refining the illuminating

stories he tells, take a look at his commentary during the period of

Barack Obama’s successful run for the presidency. It is easy to find

online, and it won him the Pulitzer Prize.

That was a moment that brought black people together, something that has

at times been compromised as the country has changed, generally for the

better. He writes: “The key thing was that we were all in the ammo boat

together, metaphorically speaking.

Racial apartheid, imposed and enforced by others, ironically had

fostered great cohesion among African Americans, binding together social

and economic classes that otherwise might have drifted apart. One

unintended impact of laws and customs mandating racial segregation was

to create, within black America, a remarkable sense of integration.”

Disintegration also takes on irksome issues such as the invisibility of

the black middle class. It also reveals a genuine interest in clarifying

the life experiences of black women, going beyond the usual standard

tropes, something that has been traditionally lacking in the work of

many black male writers.

For example, he says: “The uncertain marriage prospects of educated,

single black women are usually presented as some sort of tragedy, but

that’s not the impression I get. I see instead a fascinating process of

self-invention, and I think I might be seeing American society’s most

radical experiment in rewriting the definitions of household, family and

fulfillment.”

The King holiday this month is the kickoff of the two months of the

year, Black History Month and Women’s History Month, that are devoted to

the stories of people who might not necessarily be a focus of attention

the rest of the year.

In terms of his own personal history as the son of a librarian and a

hard-working teacher, the values of hard work, education and the

responsibility of giving back to the community were considered basic

requirements for an ethical and successful life.

As the faces of black America change, these kinds of responsibilities

that successful African American parents have always instilled in their

children may be changing as well, in ways large and small.

“Now that disintegration has cleaved one black America into four, will

we still nod to each other when we pass on the street?” He asks. I like

to think the answer is yes. More importantly, inspired by the kind of

commitment that Eugene Robinson has shown, stories will be told. Yes,

more stories will be told.

Disintegration by Eugene Robinson; Doubleday; 224 pages; $24.95